Virus Validates Trail of Ancient Human Migration

|

By LabMedica International staff writers Posted on 04 Nov 2013 |

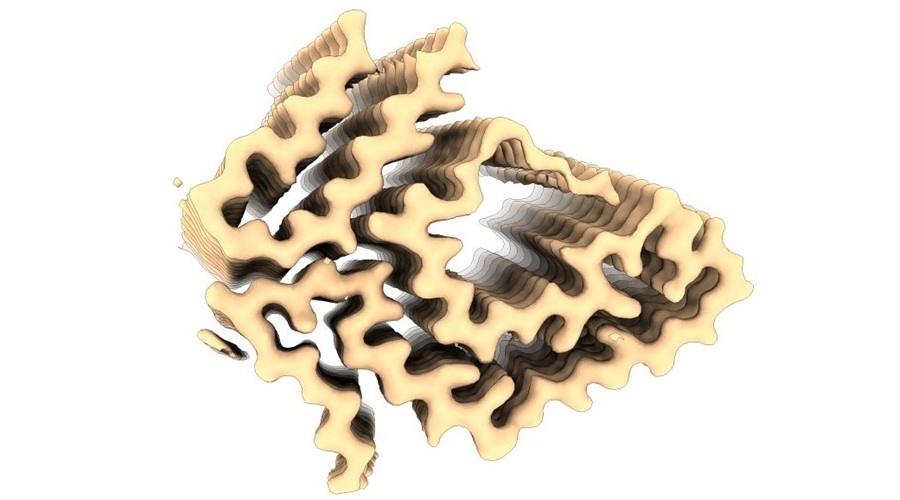

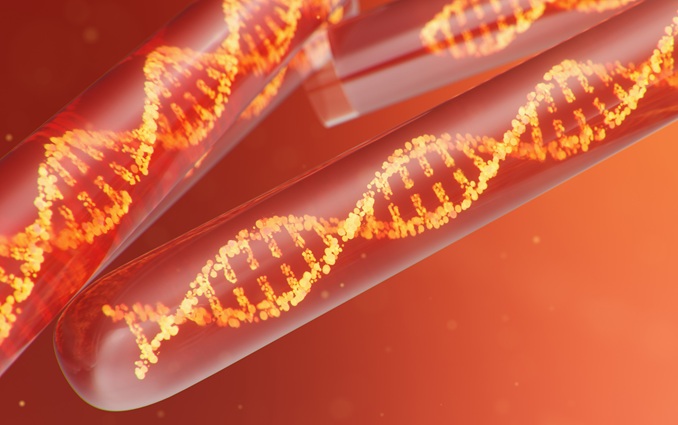

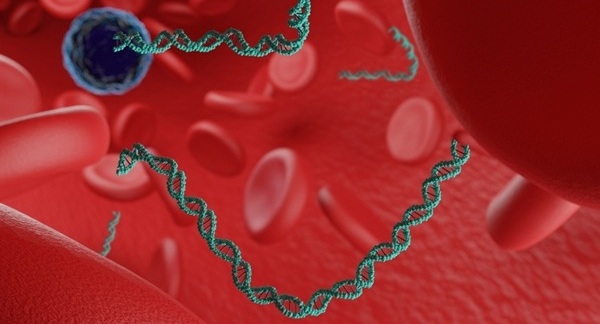

Image: World map featuring the geographic location of the six HSV-1 clades with respect to human migration: the phylogenetic data supports the “out of Africa model” of human migration with HSV-1 traveling and diversifying with its human host. Each clade is depicted by a roman numeral inside a circle. Land migration is depicted by yellow lines and air/sea migration is shown by the pink line. (Photo courtesy of Aaron W. Kolb, Cécile Ané, Curtis R. Brandt. Using HSV-1 Genome Phylogenetics to Track Past Human Migrations. PLoS ONE, 2013; 8 (10): e76267 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076267).

A research project encompassing the full genetic code of a common herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has provided a fascinating corroboration of the “out-of-Africa” pattern of human migration, which had earlier been documented by anthropologists and analyses of the human genome.

HSV-1 typically causes nothing more severe than cold sores around the mouth, according to Dr. Curtis Brandt, a professor of medical microbiology and ophthalmology at the University of Wisconsin (UW)-Madison (USA). Dr. Brandt is senior author of the study, published online October 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE.

When Dr. Brandt and coauthors Drs. Aaron Kolb and Cécile Ané compared 31 strains of HSV-1 collected in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia, “the result was fairly stunning” stated Dr. Brandt. “The viral strains sort exactly as you would predict based on sequencing of human genomes. We found that all of the African isolates cluster together, all the virus from the Far East, Korea, Japan, China clustered together, all the viruses in Europe and America, with one exception, clustered together. What we found follows exactly what the anthropologists have told us, and the molecular geneticists who have analyzed the human genome have told us, about where humans originated and how they spread across the planet,” said Dr. Brandt.

Geneticists explore how organisms are related by studying changes in the sequence of bases (letters) on their genes. From knowledge of how rapidly a specific genome changes, they can build a “family tree” that shows when specific variants had their last common ancestor. Studies of human genomes have shown that human ancestors emerged from Africa approximately 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, and then spread eastward toward Asia, and westward toward Europe.

Scientists have earlier researched herpes simplex virus type 1 by looking at one specific gene, or a small cluster of genes, however, Dr. Brandt noted that this approach can be misleading. “Scientists have come to realize that the relationships you get back from a single gene, or a small set of genes, are not very accurate.”

The study employed high-capacity genetic sequencing and advanced bioinformatics to analyze the massive amount of data from the 31 genomes. “Our results clearly support the anthropologic data, and other genetic data, that explain how humans came from Africa into the Middle East and started to spread from there.”

The technology of simultaneously comparing the entire genomes of related viruses could also be helpful in determining why specific strains of a virus are so much more lethal than others. In a tiny proportion of cases, for example, HSV-1 can cause a lethal brain infection, Dr. Brandt reported. “We’d like to understand why these few viruses are so dangerous, when the predominant course of herpes is so mild. We believe that a difference in the gene sequence is determining the outcome, and we are interested in sorting this out,” he said.

For studies of influenza virus in particular, Dr. Brandt said, “people are trying to come up with virulence markers that will enable us to predict what a particular strain of virus will do.”

The researchers broke down the HSV-1 genome into 26 pieces, made family trees for each piece, and then combined each of the trees into one network tree of the whole genome, according to Dr. Brandt. “Cécile Ané did a great job in coming up with a new way to look at these trees, and identifying the most probable grouping.” It was this grouping that paralleled existing analyses of human migration.

The new analysis could even detect some complexities of migration. Every HSV-1 sample from the United States except one correlated with the European strains, but one strain that was isolated in Texas looked Asian. “How did we get an Asian-related virus in Texas?” Dr. Kolb questioned. Either the sample had come from someone who had travelled from the Far East, or it came from a native American whose ancestors had crossed the “land bridge” across the Bering Strait approximately 15,000 years ago.

“We found support for the land bridge hypothesis because the date of divergence from its most recent Asian ancestor was about 15,000 years ago,” Dr. Brandt noted. “The dates match, so we postulate that this was an Amerindian virus.”

Herpes simplex virus type 1 was an ideal virus for the study because it is easy to collect, typically not deadly, and able to form lifelong latent infections. Because HSV-1 is spread by close contact, kissing, or saliva, it tends to run in families. “You can think of this as a kind of external genome,” Brandt says.

Furthermore, HSV-1 is much simpler than the human genome, which slashes the cost of sequencing; however, its genome is much larger than another virus that also has been used for this type of study. Genetics frequently breaks down to a numbers game; larger numbers produce stronger evidence, so a larger genome generates much more detail.

But what really excited the investigators of the study, Dr. Brandt stated, “was clear support for the out-of-Africa hypothesis. Our results clearly support the anthropological data, and other genetic data, that explain how humans came from Africa into the Middle East and started to spread from there.”

In the virus, as in human genomes, a small human population entered the Middle East from Africa. “There is a population bottleneck between Africa and the rest of the world; very few people were involved in the initial migration from Africa,” Dr. Brandt stated. “When you look at the phylogenetic tree from the virus, it's exactly the same as what the anthropologists have told us.”

Related Links:

University of Wisconsin-Madison

HSV-1 typically causes nothing more severe than cold sores around the mouth, according to Dr. Curtis Brandt, a professor of medical microbiology and ophthalmology at the University of Wisconsin (UW)-Madison (USA). Dr. Brandt is senior author of the study, published online October 2013 in the journal PLOS ONE.

When Dr. Brandt and coauthors Drs. Aaron Kolb and Cécile Ané compared 31 strains of HSV-1 collected in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia, “the result was fairly stunning” stated Dr. Brandt. “The viral strains sort exactly as you would predict based on sequencing of human genomes. We found that all of the African isolates cluster together, all the virus from the Far East, Korea, Japan, China clustered together, all the viruses in Europe and America, with one exception, clustered together. What we found follows exactly what the anthropologists have told us, and the molecular geneticists who have analyzed the human genome have told us, about where humans originated and how they spread across the planet,” said Dr. Brandt.

Geneticists explore how organisms are related by studying changes in the sequence of bases (letters) on their genes. From knowledge of how rapidly a specific genome changes, they can build a “family tree” that shows when specific variants had their last common ancestor. Studies of human genomes have shown that human ancestors emerged from Africa approximately 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, and then spread eastward toward Asia, and westward toward Europe.

Scientists have earlier researched herpes simplex virus type 1 by looking at one specific gene, or a small cluster of genes, however, Dr. Brandt noted that this approach can be misleading. “Scientists have come to realize that the relationships you get back from a single gene, or a small set of genes, are not very accurate.”

The study employed high-capacity genetic sequencing and advanced bioinformatics to analyze the massive amount of data from the 31 genomes. “Our results clearly support the anthropologic data, and other genetic data, that explain how humans came from Africa into the Middle East and started to spread from there.”

The technology of simultaneously comparing the entire genomes of related viruses could also be helpful in determining why specific strains of a virus are so much more lethal than others. In a tiny proportion of cases, for example, HSV-1 can cause a lethal brain infection, Dr. Brandt reported. “We’d like to understand why these few viruses are so dangerous, when the predominant course of herpes is so mild. We believe that a difference in the gene sequence is determining the outcome, and we are interested in sorting this out,” he said.

For studies of influenza virus in particular, Dr. Brandt said, “people are trying to come up with virulence markers that will enable us to predict what a particular strain of virus will do.”

The researchers broke down the HSV-1 genome into 26 pieces, made family trees for each piece, and then combined each of the trees into one network tree of the whole genome, according to Dr. Brandt. “Cécile Ané did a great job in coming up with a new way to look at these trees, and identifying the most probable grouping.” It was this grouping that paralleled existing analyses of human migration.

The new analysis could even detect some complexities of migration. Every HSV-1 sample from the United States except one correlated with the European strains, but one strain that was isolated in Texas looked Asian. “How did we get an Asian-related virus in Texas?” Dr. Kolb questioned. Either the sample had come from someone who had travelled from the Far East, or it came from a native American whose ancestors had crossed the “land bridge” across the Bering Strait approximately 15,000 years ago.

“We found support for the land bridge hypothesis because the date of divergence from its most recent Asian ancestor was about 15,000 years ago,” Dr. Brandt noted. “The dates match, so we postulate that this was an Amerindian virus.”

Herpes simplex virus type 1 was an ideal virus for the study because it is easy to collect, typically not deadly, and able to form lifelong latent infections. Because HSV-1 is spread by close contact, kissing, or saliva, it tends to run in families. “You can think of this as a kind of external genome,” Brandt says.

Furthermore, HSV-1 is much simpler than the human genome, which slashes the cost of sequencing; however, its genome is much larger than another virus that also has been used for this type of study. Genetics frequently breaks down to a numbers game; larger numbers produce stronger evidence, so a larger genome generates much more detail.

But what really excited the investigators of the study, Dr. Brandt stated, “was clear support for the out-of-Africa hypothesis. Our results clearly support the anthropological data, and other genetic data, that explain how humans came from Africa into the Middle East and started to spread from there.”

In the virus, as in human genomes, a small human population entered the Middle East from Africa. “There is a population bottleneck between Africa and the rest of the world; very few people were involved in the initial migration from Africa,” Dr. Brandt stated. “When you look at the phylogenetic tree from the virus, it's exactly the same as what the anthropologists have told us.”

Related Links:

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Latest BioResearch News

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- Gene Fusion Protein Proposed as Prostate Cancer Biomarker

- NIV Test to Diagnose and Monitor Vascular Complications in Diabetes

- Semen Exosome MicroRNA Proves Biomarker for Prostate Cancer

- Genetic Loci Link Plasma Lipid Levels to CVD Risk

- Newly Identified Gene Network Aids in Early Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Link Confirmed between Living in Poverty and Developing Diseases

- Genomic Study Identifies Kidney Disease Loci in Type I Diabetes Patients

- Liquid Biopsy More Effective for Analyzing Tumor Drug Resistance Mutations

- New Liquid Biopsy Assay Reveals Host-Pathogen Interactions

- Method Developed for Enriching Trophoblast Population in Samples

Channels

Clinical Chemistry

view channel

New PSA-Based Prognostic Model Improves Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment

Prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death among American men, and about one in eight will be diagnosed in their lifetime. Screening relies on blood levels of prostate-specific antigen... Read more

Extracellular Vesicles Linked to Heart Failure Risk in CKD Patients

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects more than 1 in 7 Americans and is strongly associated with cardiovascular complications, which account for more than half of deaths among people with CKD.... Read moreMolecular Diagnostics

view channel

Diagnostic Device Predicts Treatment Response for Brain Tumors Via Blood Test

Glioblastoma is one of the deadliest forms of brain cancer, largely because doctors have no reliable way to determine whether treatments are working in real time. Assessing therapeutic response currently... Read more

Blood Test Detects Early-Stage Cancers by Measuring Epigenetic Instability

Early-stage cancers are notoriously difficult to detect because molecular changes are subtle and often missed by existing screening tools. Many liquid biopsies rely on measuring absolute DNA methylation... Read more

“Lab-On-A-Disc” Device Paves Way for More Automated Liquid Biopsies

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny particles released by cells into the bloodstream that carry molecular information about a cell’s condition, including whether it is cancerous. However, EVs are highly... Read more

Blood Test Identifies Inflammatory Breast Cancer Patients at Increased Risk of Brain Metastasis

Brain metastasis is a frequent and devastating complication in patients with inflammatory breast cancer, an aggressive subtype with limited treatment options. Despite its high incidence, the biological... Read moreHematology

view channel

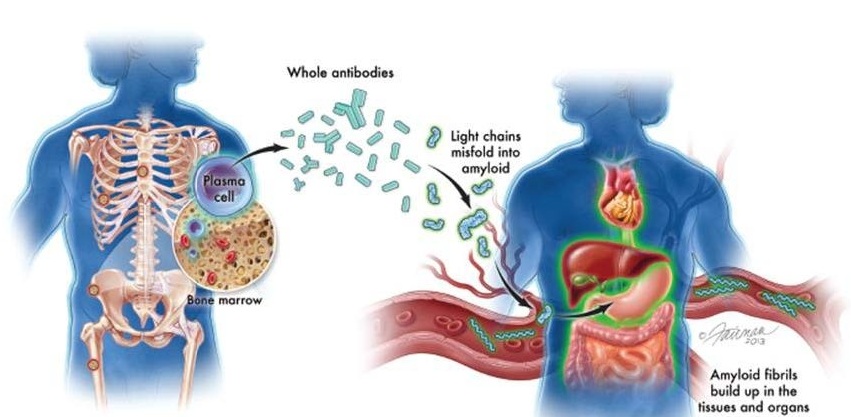

New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is a rare, life-threatening bone marrow disorder in which abnormal amyloid proteins accumulate in organs. Approximately 3,260 people in the United States are diagnosed... Read more

Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

Blood transfusions are a cornerstone of modern medicine, yet red blood cells can deteriorate quietly while sitting in cold storage for weeks. Although blood units have a fixed expiration date, cells from... Read more

Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

High-volume hemostasis sections must sustain rapid turnaround while managing reruns and reflex testing. Manual tube handling and preanalytical checks can strain staff time and increase opportunities for error.... Read more

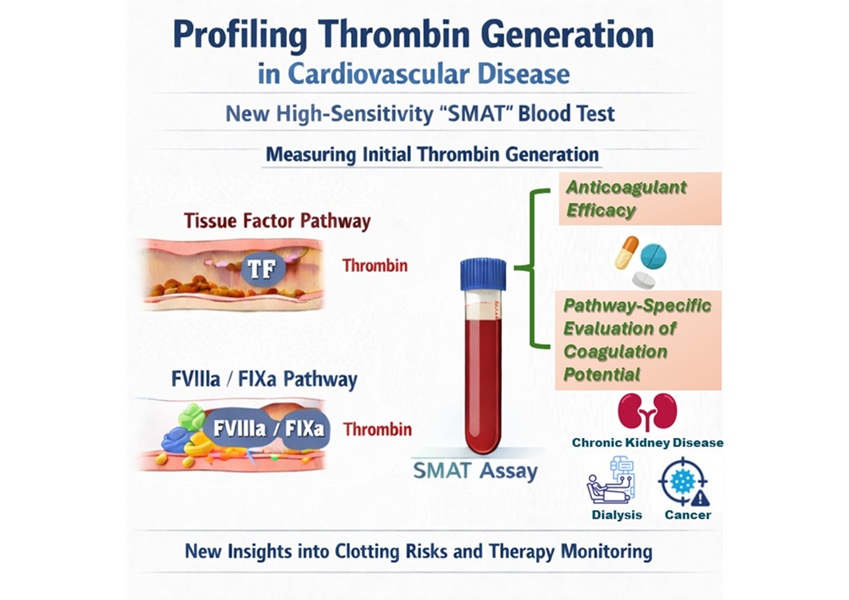

High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

Blood clotting is essential for preventing bleeding, but even small imbalances can lead to serious conditions such as thrombosis or dangerous hemorrhage. In cardiovascular disease, clinicians often struggle... Read moreImmunology

view channelBlood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive disease with limited treatment options, and even newly approved immunotherapies do not benefit all patients. While immunotherapy can extend survival for some,... Read more

Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

Targeted cancer therapies such as PARP inhibitors can be highly effective, but only for patients whose tumors carry specific DNA repair defects. Identifying these patients accurately remains challenging,... Read more

Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment, but only a small proportion of patients experience lasting benefit, with response rates often remaining between 10% and 20%. Clinicians currently lack reliable... Read moreMicrobiology

view channel

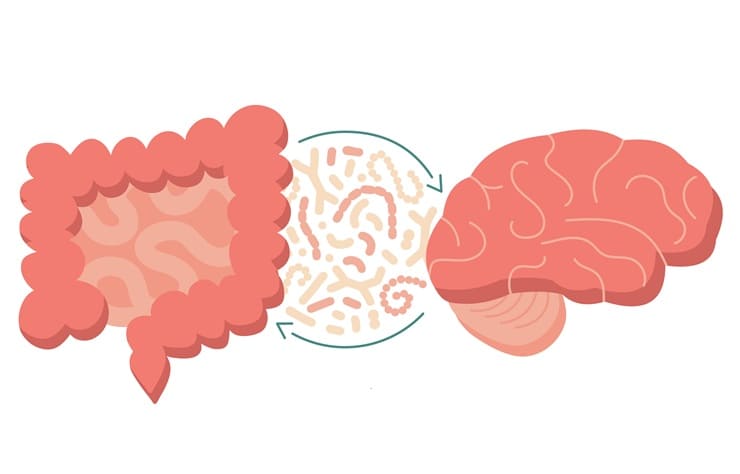

Comprehensive Review Identifies Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease affects approximately 6.7 million people in the United States and nearly 50 million worldwide, yet early cognitive decline remains difficult to characterize. Increasing evidence suggests... Read moreAI-Powered Platform Enables Rapid Detection of Drug-Resistant C. Auris Pathogens

Infections caused by the pathogenic yeast Candida auris pose a significant threat to hospitalized patients, particularly those with weakened immune systems or those who have invasive medical devices.... Read morePathology

view channel

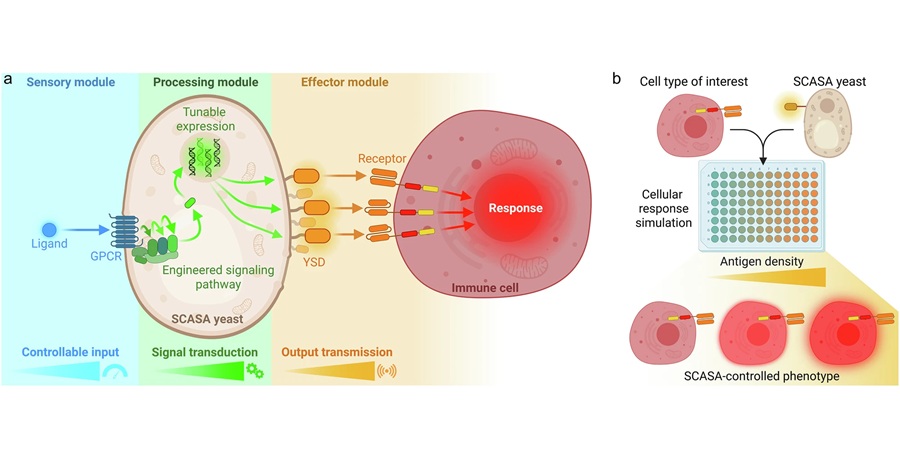

Engineered Yeast Cells Enable Rapid Testing of Cancer Immunotherapy

Developing new cancer immunotherapies is a slow, costly, and high-risk process, particularly for CAR T cell treatments that must precisely recognize cancer-specific antigens. Small differences in tumor... Read more

First-Of-Its-Kind Test Identifies Autism Risk at Birth

Autism spectrum disorder is treatable, and extensive research shows that early intervention can significantly improve cognitive, social, and behavioral outcomes. Yet in the United States, the average age... Read moreTechnology

view channel

Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

Routine diagnostic blood collection is a high‑volume task that can strain staffing and introduce human‑dependent variability, with downstream implications for sample quality and patient experience.... Read more

ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

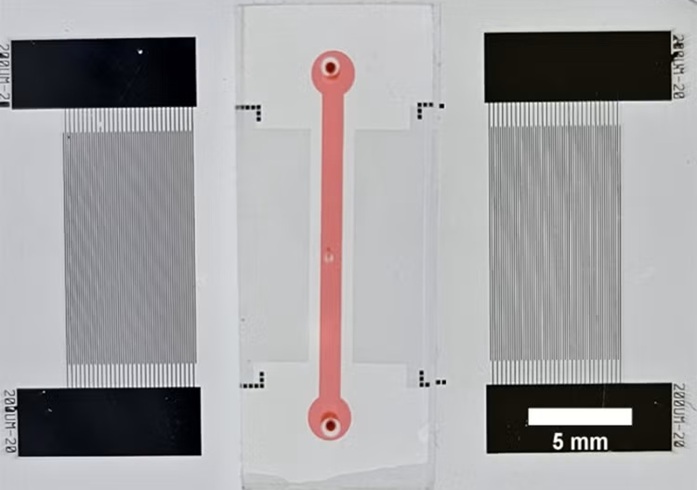

Clinical laboratories generate billions of test results each year, creating a treasure trove of data with the potential to support more personalized testing, improve operational efficiency, and enhance patient care.... Read moreAptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

Rapid and reliable virus detection is essential for controlling outbreaks, from seasonal influenza to global pandemics such as COVID-19. Conventional diagnostic methods, including cell culture, antigen... Read more

AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

Pre-eclampsia and anemia are major contributors to maternal and child mortality worldwide, together accounting for more than half a million deaths each year and leaving millions with long-term health complications.... Read moreIndustry

view channelNew Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

Mass spectrometry is a powerful analytical technique that identifies and quantifies molecules based on their mass and electrical charge. Its high selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy make it indispensable... Read more

AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

Noul Co., a Korean company specializing in AI-based blood and cancer diagnostics, announced it will supply its intelligence (AI)-based miLab CER cervical cancer diagnostic solution to Mexico under a multi‑year... Read more

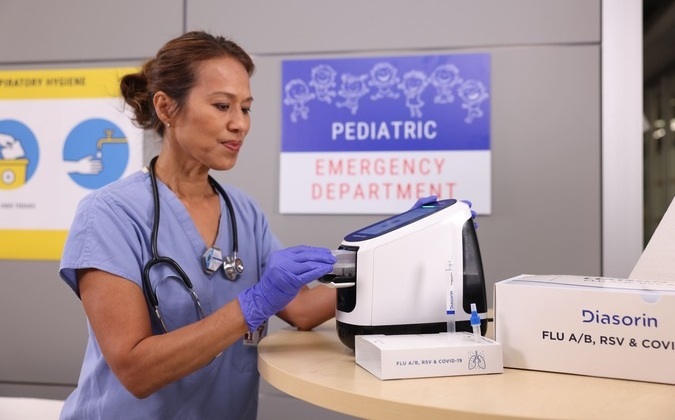

Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

Diasorin (Saluggia, Italy) has entered into an exclusive distribution agreement with Fisher Scientific, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), for the LIAISON NES molecular point-of-care... Read more