Autistic Youngsters Found to Have Too Many Brain Synapses

|

By LabMedica International staff writers Posted on 02 Sep 2014 |

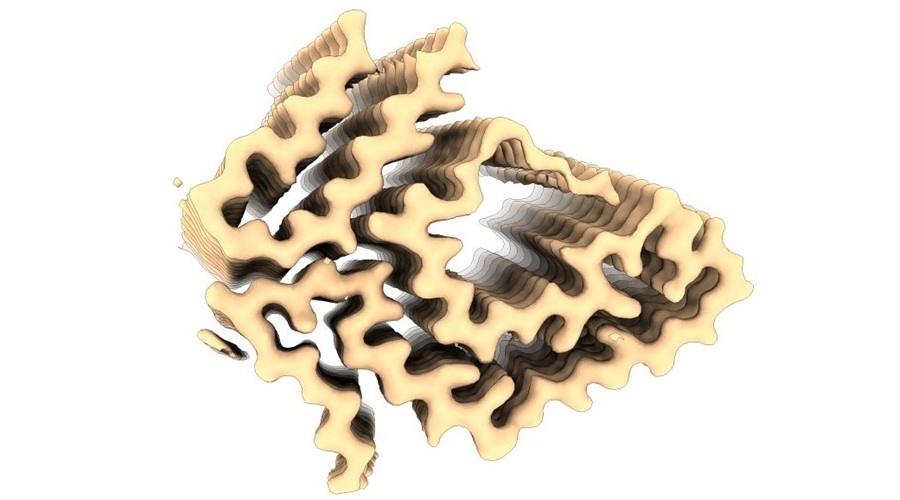

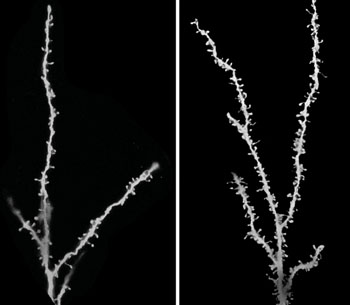

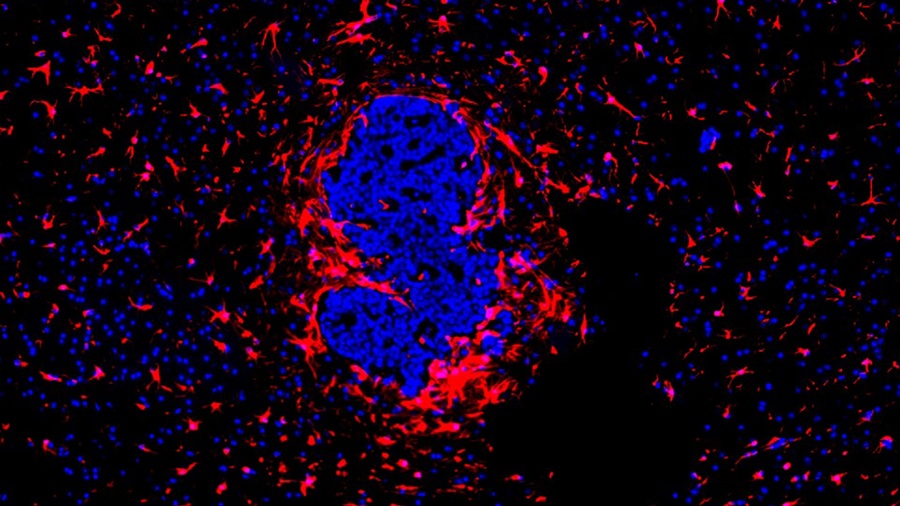

Image: (Left) Neurons in brains from people with autism do not undergo normal pruning during childhood and adolescence. The images show representative neurons from unaffected brains (left) and brains from autistic patients (right); the spines on the neurons indicate the location of synapses (Photo courtesy of Guomei Tang, PhD and Mark S. Sonders, PhD, Columbia University Medical Center).

Image: Researchers found more spines in children with autism. Spines branch out from one neuron and receive signals from other neurons through connections called synapses, so more spines indicate more synapses (Photo courtesy of Guomei Tang, PhD, and Mark S. Sonders, PhD, Columbia University Medical Center).

Autistic children and adolescents have been shown to have an excess of brain synapses, and this is due to a slowdown in the normal brain “trimming” process during development, according to new findings.

Neuroscientists from Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC; New York, NY, USA) conducted the research. Because synapses are the points where neurons connect and communicate with each other, the excessive synapses may have profound effects on how the brain functions. The study was published in the August 21, 2014, online issue of the journal Neuron.

The agent that restores normal synaptic pruning can improve autistic-like behaviors in mice, the researchers discovered; even when the drug is given after the behavior has appeared. “This is an important finding that could lead a professor and chair of psychiatry at CUMC and director of New York State Psychiatric Institute, who was not involved in the study.

Although the drug, rapamycin, has side effects that may preclude its use in people with autism, “the fact that we can see changes in behavior suggests that autism may still be treatable after a child is diagnosed, if we can find a better drug,” said the study’s senior investigator, David Sulzer, PhD, professor of neurobiology in the departments of psychiatry, neurology, and pharmacology at CUMC.

During normal brain development, a burst of synapse formation occurs in infancy, particularly in the cortex, a region involved in autistic behaviors; pruning eliminates about half of these cortical synapses by late adolescence. Synapses are known to be affected by many genes associated with autism, and some researchers have theorized that individuals with autism may have more synapses.

To evaluate this theory, coauthor Guomei Tang, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at CUMC, examined brains from children with autism who had died from other causes. Thirteen brains came from children ages 2 to 9, and 13 brains came from children ages 13 to 20. Twenty-two brains from children without autism were also examined for comparison.

Dr. Tang measured synapse density in a small section of tissue in each brain by counting the number of tiny spines that branch from these cortical neurons; each spine connects with another neuron via a synapse. By late childhood, spine density had decreased by approximately 50% in the control subjects’ brains, but by only 16% in the brains from autism patients. “It’s the first time that anyone has looked for, and seen, a lack of pruning during development of children with autism,” Dr. Sulzer said, “although lower numbers of synapses in some brain areas have been detected in brains from older patients and in mice with autistic-like behaviors.”

Insights into what caused the pruning defect were also found in the patients’ brains; the autistic children’s brain cells were filled with old and injured areas and were very deficient in a degradation pathway known as “autophagy.”

Utilizing mouse models of autism, the researchers traced the pruning defect to a protein called mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin). When mTOR is overactive, they found, brain cells lose much of their “self-eating” ability. Furthermore, without this ability, the brains of the mice were pruned inadequately and contained excess synapses. “While people usually think of learning as requiring formation of new synapses, Dr. Sulzer said, “the removal of inappropriate synapses may be just as important.”

The researchers could restore normal autophagy and synaptic pruning—and reverse autistic-like behaviors in the mice—by administering rapamycin, a drug that inhibits mTOR. The drug was effective even when administered to the mice after they developed the behaviors, suggesting that such an approach may be used to treat patients even after the disorder has been diagnosed.

Because large amounts of overactive mTOR were also found in almost all of the brains of the autism patients, the same processes may occur in children with autism. “What’s remarkable about the findings,” said Dr. Sulzer, “is that hundreds of genes have been linked to autism, but almost all of our human subjects had overactive mTOR and decreased autophagy, and all appear to have a lack of normal synaptic pruning. This says that many, perhaps the majority, of genes may converge onto this mTOR/autophagy pathway, the same way that many tributaries all lead into the Mississippi River. Overactive mTOR and reduced autophagy, by blocking normal synaptic pruning that may underlie learning appropriate behavior, may be a unifying feature of autism.”

Alan Packer, PhD, senior scientist at the Simons Foundation, which funded the research, reported that the study is an important step forward in understanding what is occurring in the brains of people with autism. “The current view is that autism is heterogeneous, with potentially hundreds of genes that can contribute. That’s a very wide spectrum, so the goal now is to understand how those hundreds of genes cluster together into a smaller number of pathways; that will give us better clues to potential treatments. The mTOR pathway certainly looks like one of these pathways. It is possible that screening for mTOR and autophagic activity will provide a means to diagnose some features of autism, and normalizing these pathways might help to treat synaptic dysfunction and treat the disease.”

Related Links:

Columbia University Medical Center

Neuroscientists from Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC; New York, NY, USA) conducted the research. Because synapses are the points where neurons connect and communicate with each other, the excessive synapses may have profound effects on how the brain functions. The study was published in the August 21, 2014, online issue of the journal Neuron.

The agent that restores normal synaptic pruning can improve autistic-like behaviors in mice, the researchers discovered; even when the drug is given after the behavior has appeared. “This is an important finding that could lead a professor and chair of psychiatry at CUMC and director of New York State Psychiatric Institute, who was not involved in the study.

Although the drug, rapamycin, has side effects that may preclude its use in people with autism, “the fact that we can see changes in behavior suggests that autism may still be treatable after a child is diagnosed, if we can find a better drug,” said the study’s senior investigator, David Sulzer, PhD, professor of neurobiology in the departments of psychiatry, neurology, and pharmacology at CUMC.

During normal brain development, a burst of synapse formation occurs in infancy, particularly in the cortex, a region involved in autistic behaviors; pruning eliminates about half of these cortical synapses by late adolescence. Synapses are known to be affected by many genes associated with autism, and some researchers have theorized that individuals with autism may have more synapses.

To evaluate this theory, coauthor Guomei Tang, PhD, assistant professor of neurology at CUMC, examined brains from children with autism who had died from other causes. Thirteen brains came from children ages 2 to 9, and 13 brains came from children ages 13 to 20. Twenty-two brains from children without autism were also examined for comparison.

Dr. Tang measured synapse density in a small section of tissue in each brain by counting the number of tiny spines that branch from these cortical neurons; each spine connects with another neuron via a synapse. By late childhood, spine density had decreased by approximately 50% in the control subjects’ brains, but by only 16% in the brains from autism patients. “It’s the first time that anyone has looked for, and seen, a lack of pruning during development of children with autism,” Dr. Sulzer said, “although lower numbers of synapses in some brain areas have been detected in brains from older patients and in mice with autistic-like behaviors.”

Insights into what caused the pruning defect were also found in the patients’ brains; the autistic children’s brain cells were filled with old and injured areas and were very deficient in a degradation pathway known as “autophagy.”

Utilizing mouse models of autism, the researchers traced the pruning defect to a protein called mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin). When mTOR is overactive, they found, brain cells lose much of their “self-eating” ability. Furthermore, without this ability, the brains of the mice were pruned inadequately and contained excess synapses. “While people usually think of learning as requiring formation of new synapses, Dr. Sulzer said, “the removal of inappropriate synapses may be just as important.”

The researchers could restore normal autophagy and synaptic pruning—and reverse autistic-like behaviors in the mice—by administering rapamycin, a drug that inhibits mTOR. The drug was effective even when administered to the mice after they developed the behaviors, suggesting that such an approach may be used to treat patients even after the disorder has been diagnosed.

Because large amounts of overactive mTOR were also found in almost all of the brains of the autism patients, the same processes may occur in children with autism. “What’s remarkable about the findings,” said Dr. Sulzer, “is that hundreds of genes have been linked to autism, but almost all of our human subjects had overactive mTOR and decreased autophagy, and all appear to have a lack of normal synaptic pruning. This says that many, perhaps the majority, of genes may converge onto this mTOR/autophagy pathway, the same way that many tributaries all lead into the Mississippi River. Overactive mTOR and reduced autophagy, by blocking normal synaptic pruning that may underlie learning appropriate behavior, may be a unifying feature of autism.”

Alan Packer, PhD, senior scientist at the Simons Foundation, which funded the research, reported that the study is an important step forward in understanding what is occurring in the brains of people with autism. “The current view is that autism is heterogeneous, with potentially hundreds of genes that can contribute. That’s a very wide spectrum, so the goal now is to understand how those hundreds of genes cluster together into a smaller number of pathways; that will give us better clues to potential treatments. The mTOR pathway certainly looks like one of these pathways. It is possible that screening for mTOR and autophagic activity will provide a means to diagnose some features of autism, and normalizing these pathways might help to treat synaptic dysfunction and treat the disease.”

Related Links:

Columbia University Medical Center

Latest BioResearch News

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- Gene Fusion Protein Proposed as Prostate Cancer Biomarker

- NIV Test to Diagnose and Monitor Vascular Complications in Diabetes

- Semen Exosome MicroRNA Proves Biomarker for Prostate Cancer

- Genetic Loci Link Plasma Lipid Levels to CVD Risk

- Newly Identified Gene Network Aids in Early Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Link Confirmed between Living in Poverty and Developing Diseases

- Genomic Study Identifies Kidney Disease Loci in Type I Diabetes Patients

- Liquid Biopsy More Effective for Analyzing Tumor Drug Resistance Mutations

- New Liquid Biopsy Assay Reveals Host-Pathogen Interactions

- Method Developed for Enriching Trophoblast Population in Samples

Channels

Clinical Chemistry

view channel

New PSA-Based Prognostic Model Improves Prostate Cancer Risk Assessment

Prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death among American men, and about one in eight will be diagnosed in their lifetime. Screening relies on blood levels of prostate-specific antigen... Read more

Extracellular Vesicles Linked to Heart Failure Risk in CKD Patients

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects more than 1 in 7 Americans and is strongly associated with cardiovascular complications, which account for more than half of deaths among people with CKD.... Read moreMolecular Diagnostics

view channel

Diagnostic Device Predicts Treatment Response for Brain Tumors Via Blood Test

Glioblastoma is one of the deadliest forms of brain cancer, largely because doctors have no reliable way to determine whether treatments are working in real time. Assessing therapeutic response currently... Read more

Blood Test Detects Early-Stage Cancers by Measuring Epigenetic Instability

Early-stage cancers are notoriously difficult to detect because molecular changes are subtle and often missed by existing screening tools. Many liquid biopsies rely on measuring absolute DNA methylation... Read more

“Lab-On-A-Disc” Device Paves Way for More Automated Liquid Biopsies

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are tiny particles released by cells into the bloodstream that carry molecular information about a cell’s condition, including whether it is cancerous. However, EVs are highly... Read more

Blood Test Identifies Inflammatory Breast Cancer Patients at Increased Risk of Brain Metastasis

Brain metastasis is a frequent and devastating complication in patients with inflammatory breast cancer, an aggressive subtype with limited treatment options. Despite its high incidence, the biological... Read moreHematology

view channel

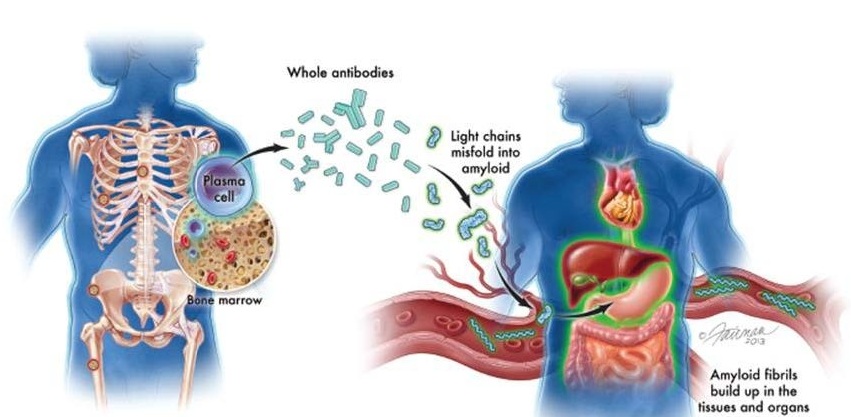

New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is a rare, life-threatening bone marrow disorder in which abnormal amyloid proteins accumulate in organs. Approximately 3,260 people in the United States are diagnosed... Read more

Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

Blood transfusions are a cornerstone of modern medicine, yet red blood cells can deteriorate quietly while sitting in cold storage for weeks. Although blood units have a fixed expiration date, cells from... Read more

Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

High-volume hemostasis sections must sustain rapid turnaround while managing reruns and reflex testing. Manual tube handling and preanalytical checks can strain staff time and increase opportunities for error.... Read more

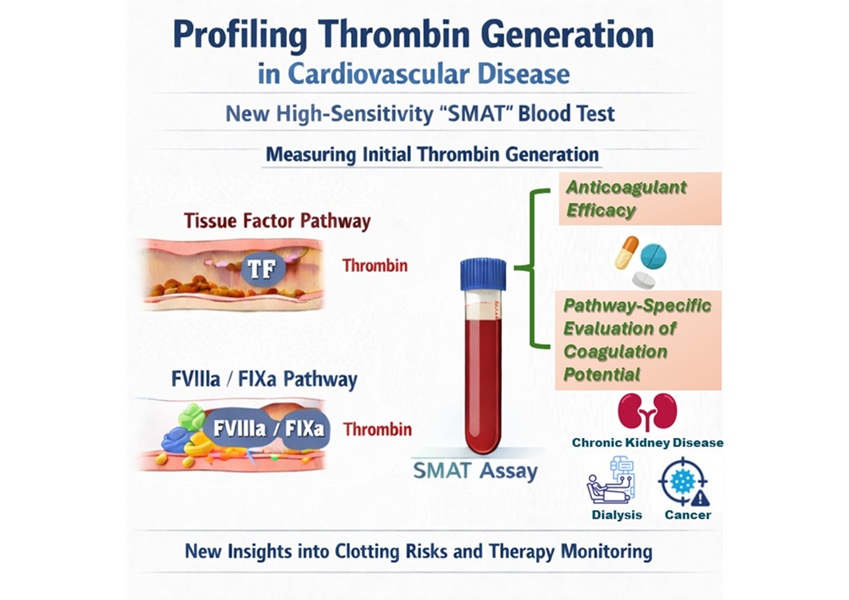

High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

Blood clotting is essential for preventing bleeding, but even small imbalances can lead to serious conditions such as thrombosis or dangerous hemorrhage. In cardiovascular disease, clinicians often struggle... Read moreImmunology

view channelBlood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive disease with limited treatment options, and even newly approved immunotherapies do not benefit all patients. While immunotherapy can extend survival for some,... Read more

Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

Targeted cancer therapies such as PARP inhibitors can be highly effective, but only for patients whose tumors carry specific DNA repair defects. Identifying these patients accurately remains challenging,... Read more

Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

Immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment, but only a small proportion of patients experience lasting benefit, with response rates often remaining between 10% and 20%. Clinicians currently lack reliable... Read moreMicrobiology

view channel

Comprehensive Review Identifies Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated With Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease affects approximately 6.7 million people in the United States and nearly 50 million worldwide, yet early cognitive decline remains difficult to characterize. Increasing evidence suggests... Read moreAI-Powered Platform Enables Rapid Detection of Drug-Resistant C. Auris Pathogens

Infections caused by the pathogenic yeast Candida auris pose a significant threat to hospitalized patients, particularly those with weakened immune systems or those who have invasive medical devices.... Read morePathology

view channel

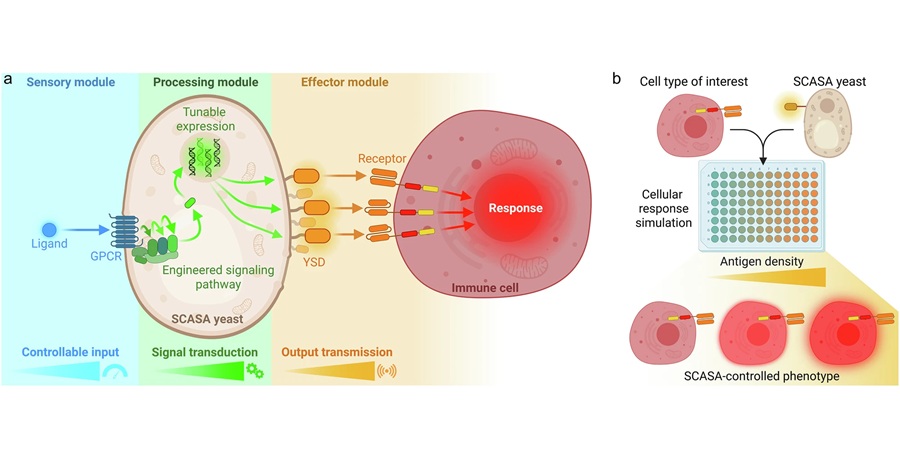

Engineered Yeast Cells Enable Rapid Testing of Cancer Immunotherapy

Developing new cancer immunotherapies is a slow, costly, and high-risk process, particularly for CAR T cell treatments that must precisely recognize cancer-specific antigens. Small differences in tumor... Read more

First-Of-Its-Kind Test Identifies Autism Risk at Birth

Autism spectrum disorder is treatable, and extensive research shows that early intervention can significantly improve cognitive, social, and behavioral outcomes. Yet in the United States, the average age... Read moreTechnology

view channel

Robotic Technology Unveiled for Automated Diagnostic Blood Draws

Routine diagnostic blood collection is a high‑volume task that can strain staffing and introduce human‑dependent variability, with downstream implications for sample quality and patient experience.... Read more

ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

Clinical laboratories generate billions of test results each year, creating a treasure trove of data with the potential to support more personalized testing, improve operational efficiency, and enhance patient care.... Read moreAptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

Rapid and reliable virus detection is essential for controlling outbreaks, from seasonal influenza to global pandemics such as COVID-19. Conventional diagnostic methods, including cell culture, antigen... Read more

AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

Pre-eclampsia and anemia are major contributors to maternal and child mortality worldwide, together accounting for more than half a million deaths each year and leaving millions with long-term health complications.... Read moreIndustry

view channelNew Collaboration Brings Automated Mass Spectrometry to Routine Laboratory Testing

Mass spectrometry is a powerful analytical technique that identifies and quantifies molecules based on their mass and electrical charge. Its high selectivity, sensitivity, and accuracy make it indispensable... Read more

AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

Noul Co., a Korean company specializing in AI-based blood and cancer diagnostics, announced it will supply its intelligence (AI)-based miLab CER cervical cancer diagnostic solution to Mexico under a multi‑year... Read more

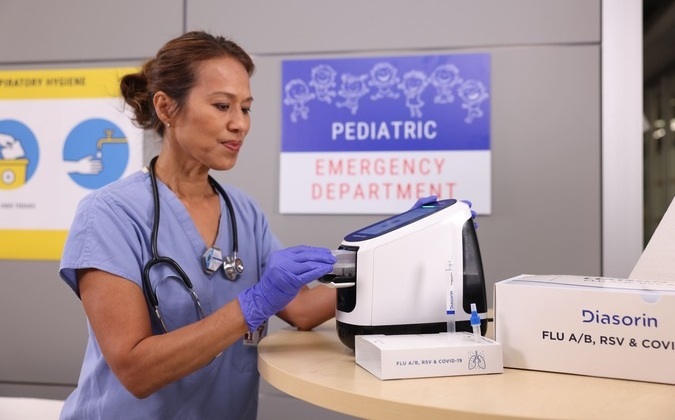

Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

Diasorin (Saluggia, Italy) has entered into an exclusive distribution agreement with Fisher Scientific, part of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), for the LIAISON NES molecular point-of-care... Read more