Computer-Designed Proteins Programmed to Deactivate Flu Viruses

|

By LabMedica International staff writers Posted on 20 Jun 2012 |

Computer-designed proteins are now being constructed to fight the flu. Researchers are demonstrating that proteins found in nature, but that do not normally bind the flu, can be engineered to act as broad-spectrum antiviral agents against a range of flu virus strains, including H1N1 pandemic influenza.

“One of these engineered proteins has a flu-fighting potency that rivals that of several human monoclonal antibodies,” said Dr. David Baker, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington (Seattle, USA), in a report June 7, 2012, published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Dr. Baker’s research team is making major inroads in optimizing the function of computer-designed influenza inhibitors. These proteins are constructed via computer modeling to fit exquisitely into a specific nano-sized target on flu viruses. By binding the target areas similar to a key into a lock, they keep the virus from changing shape, a tactic that the virus uses to infect living cells. The research efforts, analogous to docking a space station but on a molecular level, are made possible by computers that can describe the panoramas of forces involved on the submicroscopic scale.

Dr. Baker is head of the new Institute for Protein Design Center at the University of Washington. Biochemists, engineers, computer scientists, and medical specialists at the center are engineering innovative proteins with new functions for specific purposes in medicine, environmental protection, and other areas. Proteins underlie all typical activities and structures of living cells, and also control disease actions of pathogens such as viruses. Abnormal protein formation and interactions are also implicated in many inherited and later-life chronic disorders.

Because influenza is a serious worldwide public health problem due to its genetic shifts and drifts that sporadically become more virulent, the flu is one of the key interests of the Institutes for Protein Design and its collaborators in the United States and worldwide. Researchers are trying to meet the vital need for better therapeutic agents to protect against this very adaptable and extremely infective virus. Vaccines for new strains of influenza take months to develop, evaluate, and manufacture, and are not helpful for those already sick. The long response time for vaccine creation and distribution is unsettling when a more lethal strain abruptly emerges and spreads rapidly. The speed of transmission is accelerated by the lack of widespread immunity in the general population to the latest form of the virus.

Flu trackers refer to strains by their H and N subtypes. H stands for hemagglutinins, which are the molecules on the flu virus that enable it to invade the cells of respiratory passages. The virus’s hemagglutinin molecules attach to the surface of cells lining the respiratory tract. When the cell tries to engulf the virus, it makes the error of pulling it into a more acidic location. The drop in pH changes the shape of the viral hemagglutinin, thereby allowing the virus to fuse to the cell and open an entry for the virus’ RNA to come in and start making fresh viruses. It is hypothesized that the Baker Lab protein inhibits this shape change by binding the hemagglutinin in a very specific orientation and thus keeps the virus from invading cells.

Dr. Baker and his team wanted to create antivirals that could react against a wide variety of H subtypes, as this versatility could lead to a comprehensive therapy for influenza. Specifically, viruses that have hemagglutinins of the H2 subtype are responsible for the deadly pandemic of 1957 and continued to circulate until 1968. People born after that date have not been exposed to H2 viruses. The recent avian flu has a new version of H1 hemagglutinin. Data suggest that Dr. Baker’s proteins bind to all types of the group I hemagglutinin, a group that includes not only H1 but also the pandemic H2 and avian H5 strains.

The methods developed for the influenza inhibitor protein design, according to Dr. Baker, could be “a powerful route to inhibitors or binders for any surface patch on any desired target of interest.” For example, if a new disease pathogen arises, scientists could figure out how it interacts with human cells or other hosts on a molecular level. Scientists could then employ protein interface design to create a diversity of small proteins that they predict would block the pathogen’s interaction surface.

Genes for large numbers of the most promising, computer-designed proteins could be tested using yeast cells. After additional molecular chemistry research to search for the best binding among those proteins, those could be reprogrammed in the laboratory to undergo mutations, and all the mutated forms could be stored in a “library” for an in-depth examination of their amino acids, molecular architecture, and energy bonds.

Sophisticated technologies would allow the scientists to rapidly browse through the library to find those tiny proteins that clung to the pathogen surface target with pinpoint accuracy. The finalists would be selected from this pool for excelling at blocking the pathogen from attaching to, entering, and infecting human or animal cells.

The utilization of deep sequencing, the same technology now used to sequence human genomes cheaply, was particularly central in creating detailed maps relating sequencing to function. These maps were used to reprogram the design to achieve a more exact interaction between the inhibitor protein and the virus molecule. It also enabled the scientists, they said, “to leapfrog over bottlenecks” to improve the activity of the binder. They were able to see how small contributions from many small alterations in the protein, too difficult to see individually, could together create a binder with better attachment strength.

“We anticipate that our approach combining computational design followed by comprehensive energy landscape mapping,” Dr. Baker said, “will be widely useful in generating high-affinity and high-specificity binders to a broad range of targets for use in therapeutics and diagnostics.”

Related Links:

University of Washington

“One of these engineered proteins has a flu-fighting potency that rivals that of several human monoclonal antibodies,” said Dr. David Baker, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington (Seattle, USA), in a report June 7, 2012, published in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

Dr. Baker’s research team is making major inroads in optimizing the function of computer-designed influenza inhibitors. These proteins are constructed via computer modeling to fit exquisitely into a specific nano-sized target on flu viruses. By binding the target areas similar to a key into a lock, they keep the virus from changing shape, a tactic that the virus uses to infect living cells. The research efforts, analogous to docking a space station but on a molecular level, are made possible by computers that can describe the panoramas of forces involved on the submicroscopic scale.

Dr. Baker is head of the new Institute for Protein Design Center at the University of Washington. Biochemists, engineers, computer scientists, and medical specialists at the center are engineering innovative proteins with new functions for specific purposes in medicine, environmental protection, and other areas. Proteins underlie all typical activities and structures of living cells, and also control disease actions of pathogens such as viruses. Abnormal protein formation and interactions are also implicated in many inherited and later-life chronic disorders.

Because influenza is a serious worldwide public health problem due to its genetic shifts and drifts that sporadically become more virulent, the flu is one of the key interests of the Institutes for Protein Design and its collaborators in the United States and worldwide. Researchers are trying to meet the vital need for better therapeutic agents to protect against this very adaptable and extremely infective virus. Vaccines for new strains of influenza take months to develop, evaluate, and manufacture, and are not helpful for those already sick. The long response time for vaccine creation and distribution is unsettling when a more lethal strain abruptly emerges and spreads rapidly. The speed of transmission is accelerated by the lack of widespread immunity in the general population to the latest form of the virus.

Flu trackers refer to strains by their H and N subtypes. H stands for hemagglutinins, which are the molecules on the flu virus that enable it to invade the cells of respiratory passages. The virus’s hemagglutinin molecules attach to the surface of cells lining the respiratory tract. When the cell tries to engulf the virus, it makes the error of pulling it into a more acidic location. The drop in pH changes the shape of the viral hemagglutinin, thereby allowing the virus to fuse to the cell and open an entry for the virus’ RNA to come in and start making fresh viruses. It is hypothesized that the Baker Lab protein inhibits this shape change by binding the hemagglutinin in a very specific orientation and thus keeps the virus from invading cells.

Dr. Baker and his team wanted to create antivirals that could react against a wide variety of H subtypes, as this versatility could lead to a comprehensive therapy for influenza. Specifically, viruses that have hemagglutinins of the H2 subtype are responsible for the deadly pandemic of 1957 and continued to circulate until 1968. People born after that date have not been exposed to H2 viruses. The recent avian flu has a new version of H1 hemagglutinin. Data suggest that Dr. Baker’s proteins bind to all types of the group I hemagglutinin, a group that includes not only H1 but also the pandemic H2 and avian H5 strains.

The methods developed for the influenza inhibitor protein design, according to Dr. Baker, could be “a powerful route to inhibitors or binders for any surface patch on any desired target of interest.” For example, if a new disease pathogen arises, scientists could figure out how it interacts with human cells or other hosts on a molecular level. Scientists could then employ protein interface design to create a diversity of small proteins that they predict would block the pathogen’s interaction surface.

Genes for large numbers of the most promising, computer-designed proteins could be tested using yeast cells. After additional molecular chemistry research to search for the best binding among those proteins, those could be reprogrammed in the laboratory to undergo mutations, and all the mutated forms could be stored in a “library” for an in-depth examination of their amino acids, molecular architecture, and energy bonds.

Sophisticated technologies would allow the scientists to rapidly browse through the library to find those tiny proteins that clung to the pathogen surface target with pinpoint accuracy. The finalists would be selected from this pool for excelling at blocking the pathogen from attaching to, entering, and infecting human or animal cells.

The utilization of deep sequencing, the same technology now used to sequence human genomes cheaply, was particularly central in creating detailed maps relating sequencing to function. These maps were used to reprogram the design to achieve a more exact interaction between the inhibitor protein and the virus molecule. It also enabled the scientists, they said, “to leapfrog over bottlenecks” to improve the activity of the binder. They were able to see how small contributions from many small alterations in the protein, too difficult to see individually, could together create a binder with better attachment strength.

“We anticipate that our approach combining computational design followed by comprehensive energy landscape mapping,” Dr. Baker said, “will be widely useful in generating high-affinity and high-specificity binders to a broad range of targets for use in therapeutics and diagnostics.”

Related Links:

University of Washington

Latest BioResearch News

- Barcoded DNA Sheds Light on Hidden Complexities in Breast Cancer Detection

- CRISPR-Based Platform Pinpoints Drivers of Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Patient Cells

- Protective Brain Protein Emerges as Biomarker Target in Alzheimer’s Disease

- Genome Analysis Predicts Likelihood of Neurodisability in Oxygen-Deprived Newborns

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- Gene Fusion Protein Proposed as Prostate Cancer Biomarker

- NIV Test to Diagnose and Monitor Vascular Complications in Diabetes

- Semen Exosome MicroRNA Proves Biomarker for Prostate Cancer

- Genetic Loci Link Plasma Lipid Levels to CVD Risk

- Newly Identified Gene Network Aids in Early Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Link Confirmed between Living in Poverty and Developing Diseases

- Genomic Study Identifies Kidney Disease Loci in Type I Diabetes Patients

Channels

Clinical Chemistry

view channelNew Blood Test Index Offers Earlier Detection of Liver Scarring

Metabolic fatty liver disease is highly prevalent and often silent, yet it can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver failure. Current first-line blood test scores frequently return indeterminate results,... Read more

Electronic Nose Smells Early Signs of Ovarian Cancer in Blood

Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed at a late stage because its symptoms are vague and resemble those of more common conditions. Unlike breast cancer, there is currently no reliable screening method, and... Read moreMolecular Diagnostics

view channel

Blood Test Could Spot Common Post-Surgery Condition Early

Heterotopic ossification (HO), the abnormal formation of bone in soft tissue, is a common complication following hip replacement surgery. The condition affects nearly one in three patients and can lead... Read more

New Blood Test Can Help Predict Testicular Cancer Recurrence

Stage 1 testicular germ cell tumor is typically treated with surgery followed by active surveillance. Although most patients experience strong long-term outcomes, about one in four will see their cancer... Read more

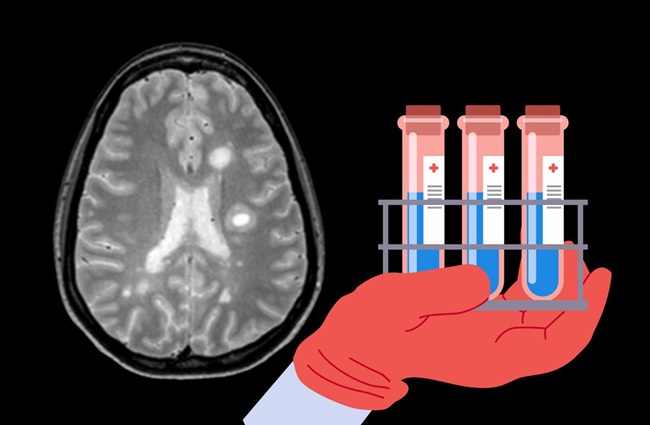

New Test Detects Alzheimer’s by Analyzing Altered Protein Shapes in Blood

Alzheimer’s disease begins developing years before memory loss or other symptoms become visible. Misfolded proteins gradually accumulate in the brain, disrupting normal cellular processes.... Read more

New Diagnostic Markers for Multiple Sclerosis Discovered in Cerebrospinal Fluid

Multiple sclerosis (MS) affects nearly three million people worldwide and can cause symptoms such as numbness, visual disturbances, fatigue, and neurological disability. Diagnosing the disease can be challenging... Read moreHematology

view channel

Rapid Cartridge-Based Test Aims to Expand Access to Hemoglobin Disorder Diagnosis

Sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia are hemoglobin disorders that often require referral to specialized laboratories for definitive diagnosis, delaying results for patients and clinicians.... Read more

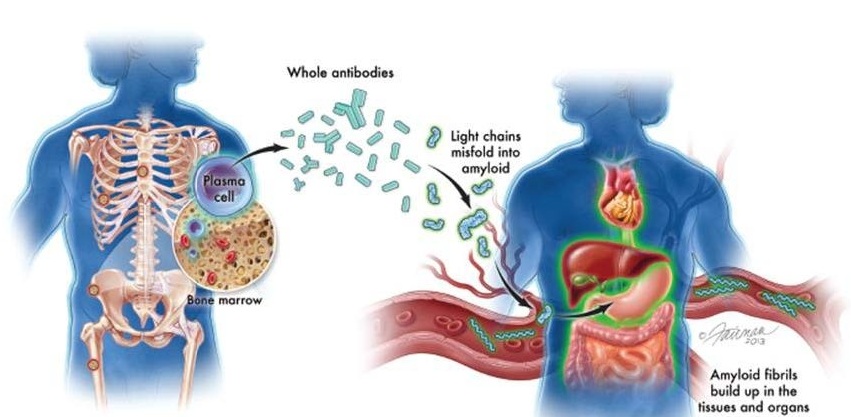

New Guidelines Aim to Improve AL Amyloidosis Diagnosis

Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is a rare, life-threatening bone marrow disorder in which abnormal amyloid proteins accumulate in organs. Approximately 3,260 people in the United States are diagnosed... Read moreImmunology

view channel

Cancer Mutation ‘Fingerprints’ to Improve Prediction of Immunotherapy Response

Cancer cells accumulate thousands of genetic mutations, but not all mutations affect tumors in the same way. Some make cancer cells more visible to the immune system, while others allow tumors to evade... Read more

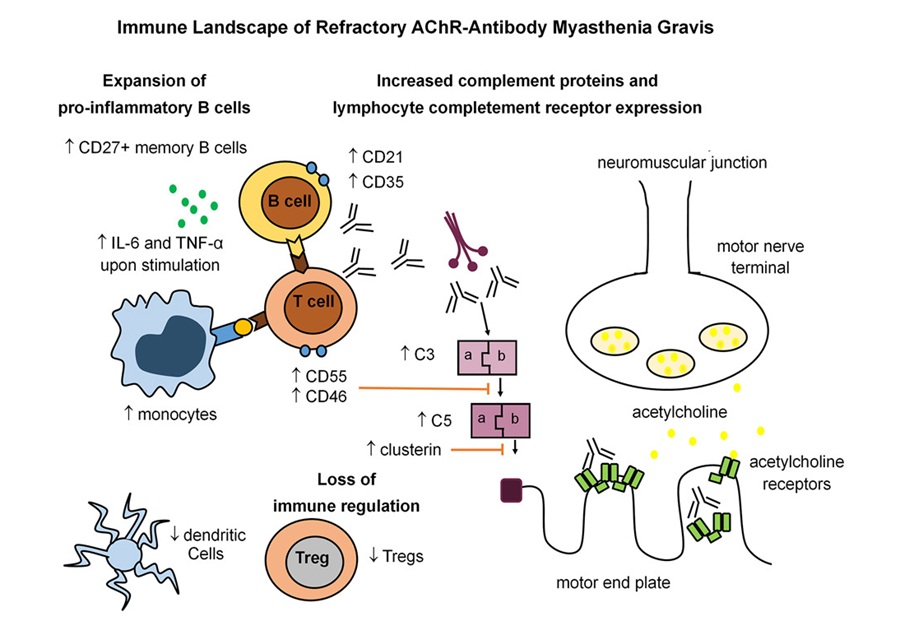

Immune Signature Identified in Treatment-Resistant Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis is a rare autoimmune disorder in which immune attack at the neuromuscular junction causes fluctuating weakness that can impair vision, movement, speech, swallowing, and breathing.... Read more

New Biomarker Predicts Chemotherapy Response in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer is an aggressive form of breast cancer in which patients often show widely varying responses to chemotherapy. Predicting who will benefit from treatment remains challenging,... Read moreBlood Test Identifies Lung Cancer Patients Who Can Benefit from Immunotherapy Drug

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is an aggressive disease with limited treatment options, and even newly approved immunotherapies do not benefit all patients. While immunotherapy can extend survival for some,... Read moreMicrobiology

view channel

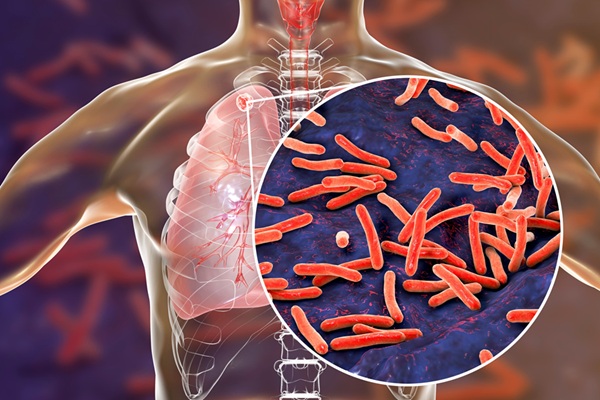

Rapid Sequencing Could Transform Tuberculosis Care

Tuberculosis remains the world’s leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, responsible for more than one million deaths each year. Diagnosing and monitoring the disease can be slow because... Read more

Blood-Based Viral Signature Identified in Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory intestinal disorder affecting approximately 0.4% of the European population, with symptoms and progression that vary widely. Although viral components of the microbiome... Read morePathology

view channel

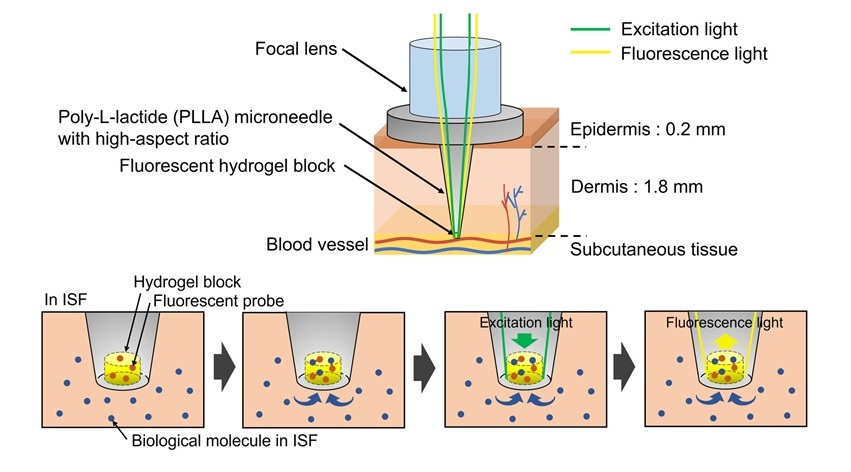

World’s First Optical Microneedle Device to Enable Blood-Sampling-Free Clinical Testing

Blood sampling is one of the most common clinical procedures, but it can be difficult or uncomfortable for many patients, especially older adults or individuals with certain medical conditions.... Read more

Pathogen-Agnostic Testing Reveals Hidden Respiratory Threats in Negative Samples

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing became widely recognized during the COVID-19 pandemic as a powerful method for detecting viruses such as SARS-CoV-2. PCR belongs to a group of diagnostic methods... Read moreTechnology

view channel

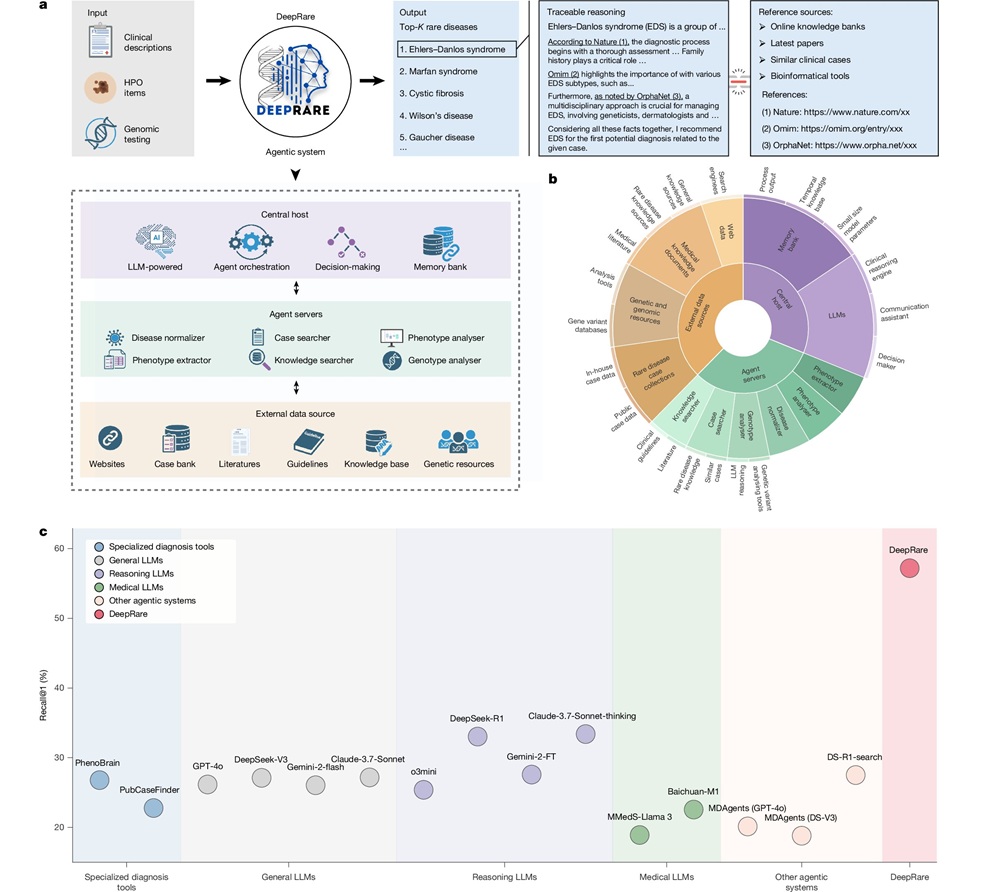

AI Model Outperforms Clinicians in Rare Disease Detection

Rare diseases affect an estimated 300 million people worldwide, yet diagnosis is often protracted and error-prone. Many conditions present with heterogeneous signs that overlap with common disorders, leading... Read more

AI-Driven Diagnostic Demonstrates High Accuracy in Detecting Periprosthetic Joint Infection

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a rare but serious complication affecting 1% to 2% of primary joint replacement surgeries. The condition occurs when bacteria or fungi infect tissues around an implanted... Read moreIndustry

view channel

Cepheid Joins CDC Initiative to Strengthen U.S. Pandemic Testing Preparednesss

Cepheid (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) has been selected by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of four national collaborators in a federal initiative to speed rapid diagnostic technologies... Read more

QuidelOrtho Collaborates with Lifotronic to Expand Global Immunoassay Portfolio

QuidelOrtho (San Diego, CA, USA) has entered a long-term strategic supply agreement with Lifotronic Technology (Shenzhen, China) to expand its global immunoassay portfolio and accelerate customer access... Read more