New Method Eliminates Unwanted Neurons from Cultures of Kidney Organoids

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 26 Nov 2018

A method has been reported that is able to eliminate more than 90% of unwanted neurons from cultures of stem cell-generated kidney cell organoids.Posted on 26 Nov 2018

Kidney organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells have great utility for investigating organ development and disease mechanisms and, potentially, as a replacement tissue source. However, it is not clear how closely organoids derived using current protocols replicate the adult human kidney.

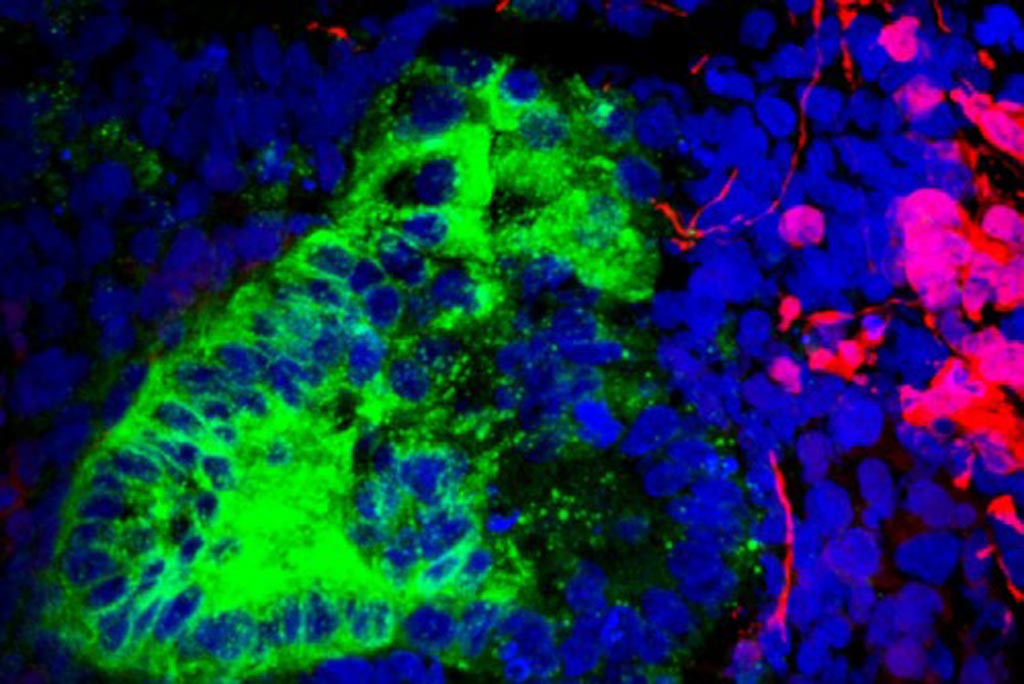

Image: A photomicrograph of a kidney organoid showing neurons in red and kidney cells in green (Photo courtesy of Humphreys Laboratory, Washington University).

To clarify this issue, investigators at Washington University (St. Louis, MO, USA) compared two directed differentiation protocols - starting from embryonic stem cells or from induced pluripotent stem cells - using single-cell transcriptomic analysis of 83,130 cells from 65 organoids. These results were matched with single-cell transcriptomes of fetal and adult kidney cells.

Results published in the November 15, 2018, online edition of the journal Cell Stem Cell revealed that both protocols generated a diverse range of kidney cells with differing ratios, but organoid-derived cell types were immature, and 10% to 20% of cells were not kidney cells.

The investigators found that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 2 (NTRK2) were expressed in the neuronal lineage during organoid differentiation. BDNF is a protein that acts on certain neurons of the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system, helping to support the survival of existing neurons, and encourage the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses. The TrkB receptor is encoded by the NTRK2 gene and is a member of a receptor family of tyrosine kinases. The activation of the BDNF-TrkB pathway is important in the development of short-term memory and the growth of neurons.

Further analysis revealed that by inhibiting the BDNF-NTRK2 pathway, it was possible to improve organoid formation by reducing neurons by 90% without affecting kidney differentiation.

“There is a lot of enthusiasm for growing organoids as models for diseases that affect people,” said senior author Dr. Benjamin D. Humphreys, professor of nephrology at Washington University. “But scientists have not fully appreciated that some of the cells that make up those organoids may not mimic what we would find in people. The good news is that with a simple intervention, we could block most of the rogue cells from growing. This should really accelerate our progress in making organoids better models for human kidney disease and drug discovery, and the same technique could be applied to targeting rogue cells in other organoids.”

“Progress to develop better treatments for kidney disease is slow because we lack good models,” said Dr. Humphreys. “We rely on mice and rats, and they are not little humans. There are many examples of drugs that have done magically well at slowing or curing kidney disease in rodents but failed in clinical trials. So, the notion of channeling human stem cells to organize into a kidney-like structure is tremendously exciting because many of us feel that this potentially eliminates that "lost in translation" aspect of going from a mouse to a human.”

Related Links:

Washington University