Secondary Bile Acids in the Large Intestine Inhibit Clostridium difficile Growth

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 17 Jan 2016

Secondary bile acids that result from bacterial metabolism in the large intestine inhibit the growth of the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium difficile, but when bile acid levels are disrupted by antibiotic treatment, C. difficile is able to flourish.Posted on 17 Jan 2016

Primary bile acids are those synthesized by the liver, while secondary bile acids result from bacterial actions in the colon. So far inhibition of C. difficile growth by secondary bile acids had only been shown in vitro. To understand how this mechanism works in vivo, investigators at North Carolina State University (Raleigh, USA) and the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, USA) used targeted bile acid metabolomics to determine the physiologically relevant concentrations of primary and secondary bile acids present in the mouse small and large intestinal tracts and how these impacted C. difficile dynamics. Metabolomics is the study of chemical processes involving metabolites, while the metabolome represents the collection of all metabolites in a biological cell, tissue, organ, or organism that are the end products of cellular processes.

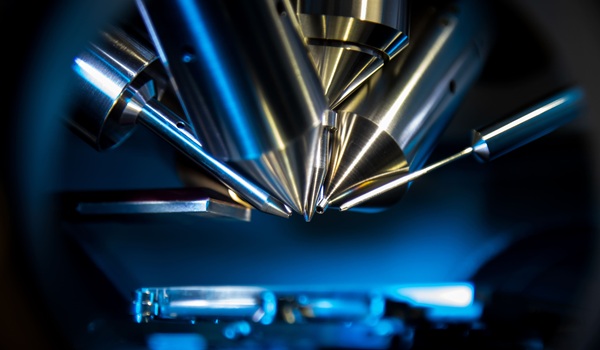

![Image: Scanning electron micrograph of Clostridium difficile bacteria from a stool sample (Photo courtesy of the CDC - [US] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Image: Scanning electron micrograph of Clostridium difficile bacteria from a stool sample (Photo courtesy of the CDC - [US] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).](https://globetechcdn.com/mobile_labmedica/images/stories/articles/article_images/2016-01-17/GMS-007.jpg)

Image: Scanning electron micrograph of Clostridium difficile bacteria from a stool sample (Photo courtesy of the CDC - [US] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

The investigators treated mice with a variety of antibiotics to create distinct microbial and metabolic (bile acid) environments and directly tested their ability to support or inhibit C. difficile spore germination and outgrowth.

They reported in the January 6, 2016, online edition of the journal mSphere that susceptibility to C. difficile in the large intestine was observed only after specific broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment (cefoperazone, clindamycin, and vancomycin) and was accompanied by a significant loss of secondary bile acids (deoxycholate, lithocholate, ursodeoxycholate, hyodeoxycholate, and omega-muricholate). These changes were correlated to the loss of specific microbiota community members, the Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae families.

Additionally, the investigators found that the physiological concentrations of secondary bile acids present in the large intestine during C. difficile resistance were able to inhibit spore germination and outgrowth in vitro. Conditions in the large intestine were different from those in the small intestine, since C. difficile spore germination and outgrowth were supported constantly in the mouse small intestine regardless of antibiotic perturbation.

"We know that within a healthy gut environment, the growth of C. difficile is inhibited," said senior author Dr. Casey Theriot, assistant professor of infectious disease at North Carolina State University. "But we wanted to learn more about the mechanisms behind that inhibitory effect. These findings are a first step in understanding how the gut microbiota regulates bile acids throughout the intestine. Hopefully they will aid the development of future therapies for C. difficile infection and other metabolically relevant disorders such as obesity and diabetes."

Related Links:

North Carolina State University

University of Michigan