Cancer Researchers Use Fluorescent Tags to Track Dispersion of Tumors During Metastasis

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 23 Aug 2015

A novel mouse cancer model was developed in which tumor cells with different mutations were labeled with specific fluorescent signals that allowed them to be traced by their unique colors as they left the site of the primary tumor and established themselves in other locations in the body.Posted on 23 Aug 2015

In order to learn whether metastasis in a mouse model depended on multiple cell types or single clones, investigators at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, USA) used a variety of fluorescent proteins to tag and track different pancreatic cancer cells as they entered the bloodstream and spread to distant organs.

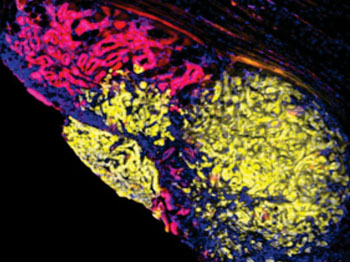

Image: Multicolored metastasis in the peritoneal lining of the abdomen comprised of red and yellow fluorescent cells demonstrating that pancreatic cancer spreads through interactions between different groups of cells (Photo courtesy of Dr. Ravi Maddipati, University of Pennsylvania).

They reported in the July 24, 2015, online edition of the journal Cancer Discovery that mutations in the Kras and p53 genes generated differently colored tumor cell populations. The mice eventually developed tumors at secondary sites including the liver, lung, peritoneum, and diaphragm. These metastases often comprised cells from tumor cell populations displaying at least two different colors. By backtracking, the investigators showed that these multicolored growths originated from circulating tumor cells that occurred as clusters of different colored cancer cells.

In some secondary sites (lung and liver), despite colonization by multicolored clusters, subsequent growth of a single colored tumor derived from physiological factors in the organ in which they now resided.

"These results provide an unprecedented window into the cellular dynamics of tumor evolution and suggest that interactions between subpopulations of tumor cell types contribute to metastatic progression from initial tumors," said senior author Dr. Ben Z. Stanger, professor of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania. "The finding that metastases are frequently polyclonal and that subsequent cellular behavior is site-dependent also gives us insight into the origins and evolution of clonal diversity in metastatic disease. If cells do cooperate during metastasis, what is the molecular basis for their communication, and can we hit that? The work also reinforces the importance of finding tumor cell clusters in the blood as a mechanism of detecting cancer metastasis earlier."

Related Links:

University of Pennsylvania