Manually Powered Device Separates Blood for Diagnosis

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 16 May 2017

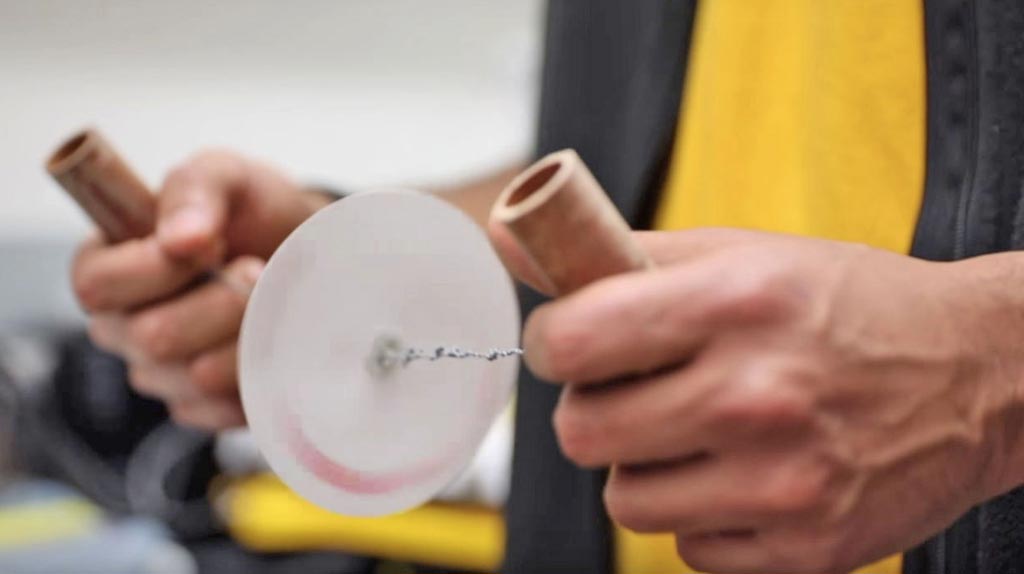

Inspired by a whirligig toy, researchers have used its mechanical principles to develop an ultra-low-cost, hand-powered blood centrifuge out of paper, no electricity required. The tool could improve diagnosis of diseases like malaria, African sleeping sickness, and tuberculosis in resource-poor, off-the-grid regions where these diseases are prevalent.Posted on 16 May 2017

Bioengineers at Stanford University built the “paperfuge” using ~ 20 US cents of paper, twine, and plastic. With rotational speeds of up to 125,000 rpm, it can exert centrifugal forces of 30,000 Gs, and can separate blood plasma from red cells in 1.5 minutes.

Image: The low-cost manual “paperfuge” was inspired by the whirligig toy, in which a loop of twine is thread through two holes in a button or disk. The loop ends are grabbed then rhythmically pulled. As the twine coils and uncoils, the button spins at a high speed. Bioengineers designed the paperfuge to concentrate parasites like malaria in blood (Photo courtesy of Stanford University).

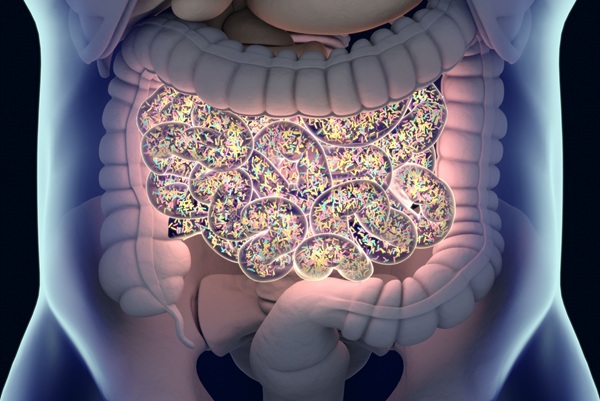

“To the best of my knowledge, it’s the fastest spinning object driven by human power,” said Manu Prakash, assistant professor at Stanford. A centrifuge is critical to separate blood fractions to make pathogens simpler to detect: red cells collect at the bottom of the tube, plasma at top, and parasites like Plasmodium settle in the middle. Prof. Prakash recognized the need for a new type of centrifuge after seeing an expensive centrifuge being used as a doorstop in a rural clinic in Uganda because there was no electricity to run it.

“There are more than a billion people around the world who have no infrastructure, no roads, no electricity,” said Prof. Prakash. He began brainstorming ideas with Saad Bhamla, postdoctoral research fellow. After exploring ways to convert human energy into spinning forces, they began focusing on toys invented before the industrial age – yo-yos, tops, and whirligigs.

“One night I was playing with a button and string, and out of curiosity, I set up a high-speed camera to see how fast a button whirligig would spin. I couldn’t believe my eyes,” said Dr. Bhamla – it was rotating at 10,000-15,000 rpm. After two weeks of prototyping, he mounted a capillary of blood on a paper-disc whirligig and was able to centrifuge blood into layers.

It was a proof-of-concept, but before moving on in the design process, he and Prof. Prakash decided to tackle a scientific question no one else had: How does a whirligig actually work?

The other “string theory”: Dr. Bhamla recruited three undergraduate engineering students from MIT (Cambridge, USA) and Stanford to build a mathematical model. The team created a computer simulation to capture design variables like disc size, string elasticity, and pulling force. They also borrowed equations from the physics of supercoiling DNA strands to understand how hand-forces move from the coiling strings to power the spinning disc.

“There are some beautiful mathematics hidden inside this object,” Prof. Prakash said. Once the engineers validated their models against real-world prototype performance, they were able to create a prototype with rotational speeds of up to 125,000 rpm, a magnitude significantly higher than their first prototypes.

“From a technical spec point of view, we can match centrifuges that cost from USD 1,000 to USD 5,000,” said Prof. Prakash.

In parallel, they improved the device’s safety and began testing configurations that could be used to test live parasites in the field. From lab-based trials, they found that malaria parasites could be separated from red blood cells in 15 minutes. And by spinning the sample in a capillary precoated with acridine orange dye, glowing parasites could be identified by simply placing the capillary under a microscope.

They are currently conducting a paperfuge field validation trial for malaria diagnostics with PIVOT and Institut Pasteur, community-health collaborators based in Madagascar.

The invention was driven by a frugal toolbox design philosophy to rethink traditional medical tools to lower costs and bring capabilities out of the lab and into hands of healthcare workers in resource-poor areas. “Frugal science is about democratizing scientific tools to get them out to people around the world,” said Prof Prakash, who also hopes these tools will someday enable carrying a complete laboratory in a backpack into remote underserved areas.

The study, by Bhamla MS et al, was published January 10, 2017, in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.