Donated Blood Could Be Transformed Into Universal Type

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 11 May 2015

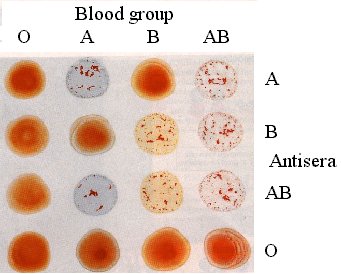

Blood transfusions are critically important in many medical procedures, but the presence of antigens on erythrocytes means that careful blood-typing must be carried out prior to transfusion to avoid adverse and sometimes fatal reactions following transfusion.Posted on 11 May 2015

Every day, thousands of people need donated blood, but only blood without A- or B-type antigens, such as type O, can be given to all of those in need, and it's usually in short supply. However an efficient way to transform A and B blood into a neutral type that can be given to any patient has been reported.

Image: Hemagglutination test of red cells used for typing ABO blood groups (Photo courtesy of University College London).

Scientists at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada) working with other Canadian and French investigators studied how to enzymatically remove the terminal N-acetylgalactosamine or galactose of A- or B-antigens, respectively, which would yield universal O-type blood. They started with the family 98 glycoside hydrolase from Streptococcus pneumoniae SP3-BS71 which cleaves the entire terminal trisaccharide antigenic determinants of both A- and B-antigens from some of the linkages on red blood cell surface glycans. Through several rounds of evolution, they developed variants with vastly improved activity toward some of the linkages that are resistant to cleavage by the wild-type enzyme.

The investigators fine-tuned one of those enzymes and improved its ability to remove type-determining sugars by 170-fold, rendering it antigen-neutral and more likely to be accepted by patients regardless of their blood type. The authors concluded that the resulting enzyme effects more complete removal of blood group antigens from cell surfaces, demonstrating the potential for engineering enzymes to generate antigen-null blood from donors of various types. In addition to blood transfusions, the scientists say their advance could potentially allow organ and tissue transplants from donors that would otherwise be mismatched. The study was published on April 14, 2015, in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Related Links:

University of British Columbia

(3) (1).png)