Immuno-CRISPR Assay Helps Diagnose Early Kidney Transplant Rejection

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 20 Jan 2022

When a patient receives a kidney transplant, doctors carefully monitor them for signs of rejection in several ways, including biopsy. However, this procedure is invasive and can only detect issues at a late stage.Posted on 20 Jan 2022

Kidney transplant recipients must take immunosuppressant drugs for the rest of their lives to help keep their immune systems from attacking the foreign organ. However, kidney rejection can still occur, particularly in the first few months after transplantation, which is known as acute rejection. Signs include increased serum creatinine levels and symptoms such as kidney pain and fever.

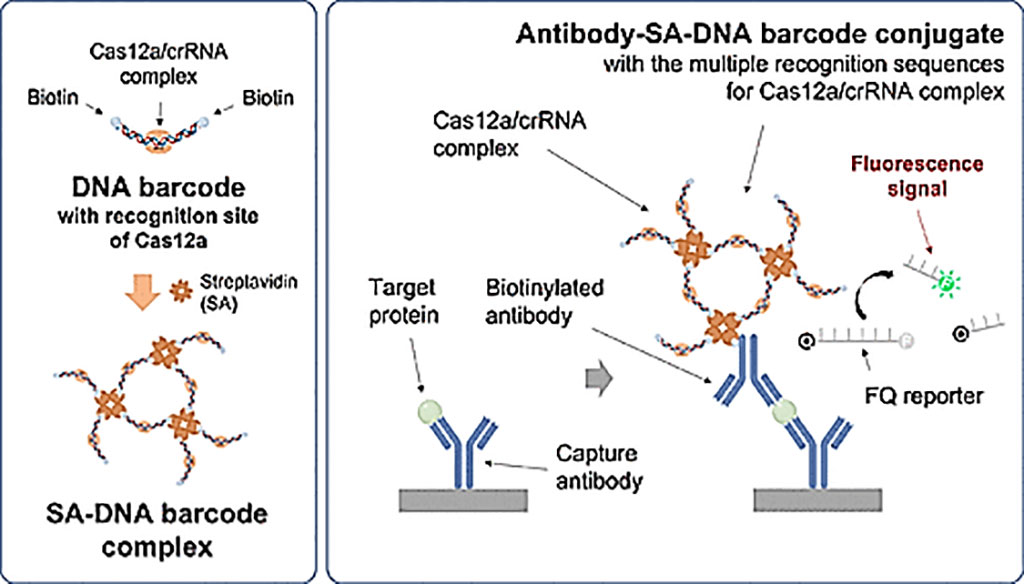

Image: Highly Sensitive Immuno-CRISPR Assay Developed for CXCL9 Detection Helps Diagnose Early Kidney Transplant Rejection (Photo courtesy of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute)

Biomedical Engineers at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Troy, NY, USA) developed a CRISPR-based assay that can sensitively and non-invasively detect a biomarker of acute kidney rejection in urine. CRISPR-based detection of target DNA or RNA exploits a dual function, including target sequence-specific recognition followed by trans-cleavage activity of a collateral single strand DNA (ssDNA) linker between a fluorophore (F) and a quencher (Q), which amplifies a fluorescent signal upon cleavage.

To establish the “immuno-CRISPR” assay, the scientists used anti-CXCL9 antibody–DNA barcode conjugates to target CXCL9 and amplify fluorescent signals via Cas12a-based trans-cleavage activity of FQ reporter substrates, respectively, and in the absence of an isothermal amplification step. To enhance detection sensitivity, the DNA barcode system was engineered by introducing multiple Cas12a recognition sites. Use of biotinylated DNA barcodes enabled self-assembly onto streptavidin (SA) to generate SA–DNA barcode complexes to increase the number and density of Cas12a recognition sites attached to biotinylated anti-CXCL9 antibody.

The investigators improved the rate of CXCL9 detection approximately 8-fold when compared to the use of a monomeric DNA barcode. The limit of detection (LOD) for CXCL9 using the immuno-CRISPR assay was 14 pg/mL, which represented an ∼7-fold improvement when compared to traditional HRP-based ELISA. Selectivity was shown with a lack of crossover reactivity with the related chemokine CXCL1. Finally, they successfully evaluated the presence of CXCL9 in urine samples from 11 kidney transplant recipients using the immuno-CRISPR assay, resulting in 100% accuracy to clinical CXCL9 determination and paving the way for use as a point-of-care noninvasive biomarker for the detection of kidney transplant rejection.

The authors concluded that importantly, unlike other CRISPR-based detection methods, PCR amplification is not required, which makes the method easier to adapt to a device that could be used in a doctor's office or even a patient's home. The study was published on December 4, 2021, in the journal Analytical Chemistry.

Related Links:

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

(3) (1).png)