Mini-Tumors Cultivated from Circulating Cancer Cells to Help Develop Targeted Therapies

Posted on 06 Jan 2025

Metastases, which are the spread of tumors to critical organs like the liver, lungs, or brain, present a major challenge in cancer treatment, as they are often difficult to manage. Despite significant progress in breast cancer treatment over recent years, metastatic breast cancer continues to pose a significant hurdle, with metastases often showing only temporary responses to therapy. These metastases begin when cancer cells detach from the original tumor and travel to other organs through the bloodstream. These circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are extremely rare and are hidden among billions of normal blood cells, making them challenging to detect and study. Until now, CTCs could not be cultured in the lab, hindering progress in understanding therapy resistance. Now, researchers have successfully cultivated stable tumor organoids directly from blood samples of breast cancer patients. Using these mini-tumors, the researchers identified a molecular signaling pathway that enables the cancer cells to survive and resist treatment. This discovery has led to the development of an approach to specifically target and eliminate these tumor cells in laboratory experiments.

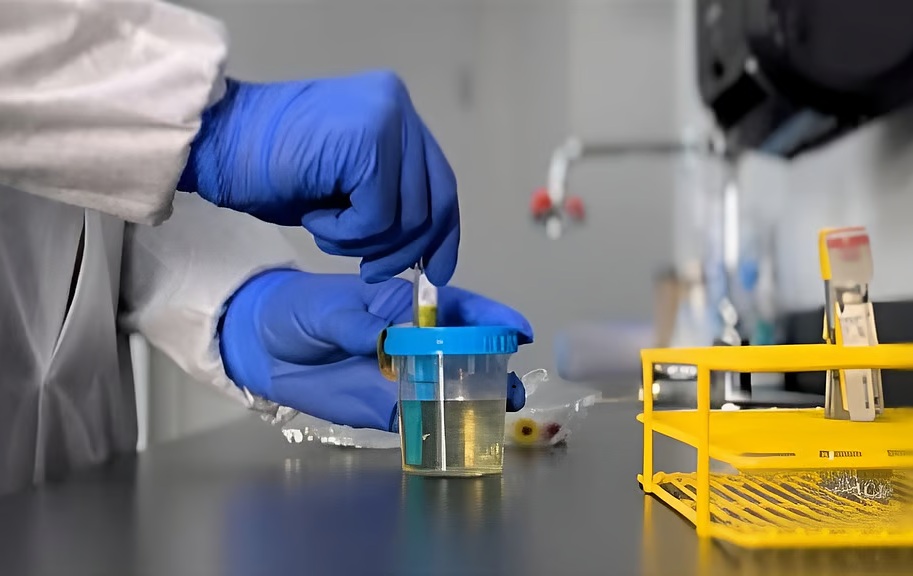

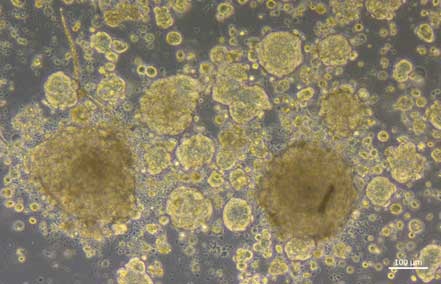

A team of researchers, including those from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany), had previously shown that only a small fraction of circulating tumor cells can form metastases in other organs. These rare "germ cells" of metastasis are resistant to treatment, difficult to isolate, and could not previously be multiplied in the laboratory, which made developing targeted therapies against them challenging. Understanding how these cells survive initial therapy and what drives their resistance could potentially help prevent breast cancer metastasis from forming in the first place. In their latest research, the team successfully cultured CTCs from breast cancer patients' blood samples and grew them into stable tumor organoids in the lab, a process that previously required a lengthy and complex procedure involving immunodeficient mice.

To study how tumor cells develop resistance to treatment, the researchers needed tumor samples from various stages of the disease. Unlike tissue biopsies, which require surgery, blood samples are simple to collect and can be taken multiple times. These three-dimensional, patient-specific organoids can be grown from blood samples repeatedly throughout the course of the disease, making them ideal for investigating the molecular mechanisms behind tumor survival despite therapy. Preclinical testing on existing cancer drugs can also be conducted efficiently and at scale using organoids in the lab. In the CATCH clinical registry trial, the genetic diversity of breast cancer cells is analyzed. Thanks to the successful cultivation of the organoids, the research team, in collaboration with the CATCH trial experts, identified a crucial signaling pathway that supports the growth and survival of CTCs in the bloodstream.

The protein NRG1 (neuregulin 1) acts as a critical "fuel" for these cells. It binds to the HER3 receptor on cancer cells and, together with the HER2 receptor, activates signaling pathways that promote cell growth and survival. Even when this "fuel" is depleted or the receptors are blocked by drugs, the cancer cells can activate alternative pathways. One such pathway, controlled by the FGFR1 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 1), ensures that the cells continue to grow and survive. This ability to adapt is a key mechanism behind therapy resistance. However, the researchers demonstrated that blocking both the NRG1-HER2/3 and FGFR pathways in the organoids could effectively stop tumor cell proliferation and induce cell death.

"The possibility of cultivating CTCs from the blood of breast cancer patients as tumor organoids in the laboratory at different time points is a decisive breakthrough. This makes it much easier to investigate how tumor cells become resistant to therapies,” said Andreas Trumpp, Head of a research division at the DKFZ and Director of HI-STEM. “On this basis, we can develop new treatments that may also specifically kill resistant tumor cells. Another conceivable approach is to adapt existing therapies in such a way that the development of resistance and metastases is reduced or even prevented from the outset. As the organoids are specific to each patient, this method is suitable for identifying or developing customized therapies that are optimally tailored to the respective diseases."