Circulating Levels of Anti-Müllerian Hormone Can Identify Premenopausal Women Prior to Significant Bone Density Loss

Posted on 07 Apr 2022

The level of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) in the blood has been linked to menopause-related bone loss and may be used to identify women who are experiencing, or about to experience, bone loss related to their transition into menopause.

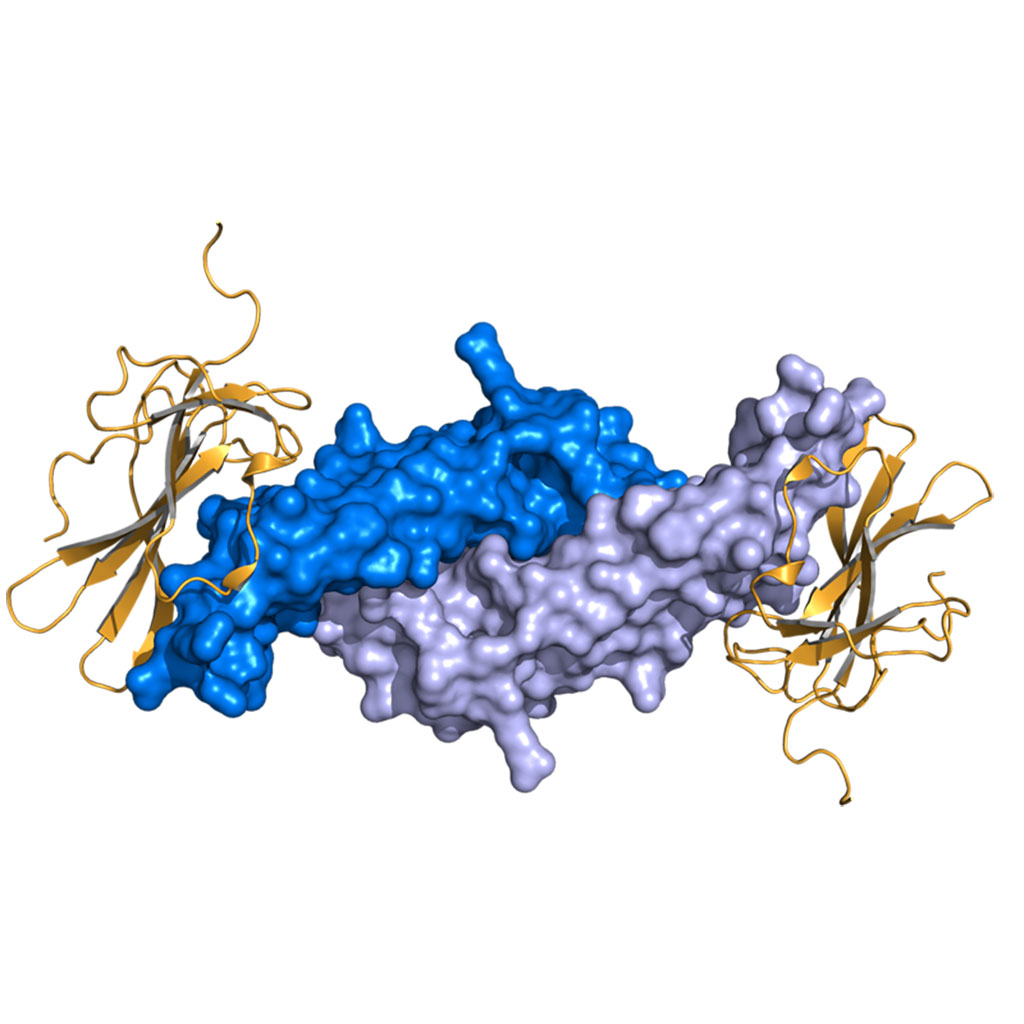

AMH is a dimeric glycoprotein consisting of two identical subunits linked by sulfide bridges, and characterized by the N-terminal and C-terminal dimers. AMH binds to its Type 2 receptor AMHR2, which phosphorylates a type I receptor under the transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) signaling pathway. In addition to other sites, AMH is a product of granulosa cells of the preantral and small antral follicles in women. As such, AMH is only present in the ovary until menopause. Production of AMH regulates folliculogenesis by inhibiting recruitment of follicles from the resting pool in order to select for the dominant follicle, after which the production of AMH diminishes. As a product of the granulosa cells, which envelop each egg and provide them energy, AMH can also serve as a molecular biomarker for relative size of the ovarian reserve. In humans, this is helpful because the number of cells in the follicular reserve can be used to predict timing of menopause.

Investigators at the University of California, Los Angeles (USA) hypothesized that low circulating levels of AMH, which decline as women approach their final menstrual period (FMP), would be associated with future and ongoing rapid bone loss. To test this theory they used data from The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation, a multisite, multi-ethnic, prospective cohort study of the menopause transition.

The data showed that 17% of premenopausal women age 42 or older will have lost a significant fraction of their peak bone mass within two to three years of the FMP. However, among those with less than 50 picograms of AMH per milliliter of blood, nearly double the percentage, 33%, will have lost a significant fraction of peak bone mass during the same time period. In addition, 42% of women in early perimenopause will have lost a significant fraction of peak bone mass within two to three years. However, among women in early perimenopause with AMH levels below 25 picograms of AMH per milliliter of blood, 65% will have lost a significant percentage of peak bone mass in that time. These findings suggest that AMH measurement can help identify women poised for significant bone loss in time for early intervention.

“Bone loss typically begins about a year before a woman’s last menstrual period,” said the first author, Dr. Arun Karlamangla, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “To be able to intervene and reduce the rate and amount of bone loss, we need to know if this loss is imminent or already ongoing. We do not reliably know before it actually happens when a woman’s last menstrual period will be, so we cannot tell whether it is time to do something about bone loss. These findings make feasible the designing and testing of midlife interventions to prevent or delay osteoporosis in women.”

The study was published in the April 4, 2022, online edition of the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Related Links:

University of California, Los Angeles