Pathogenic Antibodies to Dengue Virus Linked to Disease Severity

By LabMedica International staff writers

Posted on 09 Feb 2017

Researchers have discovered that anti-dengue IgG antibodies enhanced for FcγRIIIA binding are involved in determining severity of disease upon secondary infection. The finding helps explain why only some people develop life-threatening dengue infections.Posted on 09 Feb 2017

For most people who contract it for the first time, dengue fever is a relatively mild disease. For some, however, a subsequent infection results in a harsh and potentially fatal illness. Research from a team based at The Rockefeller University has begun to reveal why certain people are much more vulnerable to secondary infections. Their latest findings could lead to better strategies to identify and better treat those most at risk.

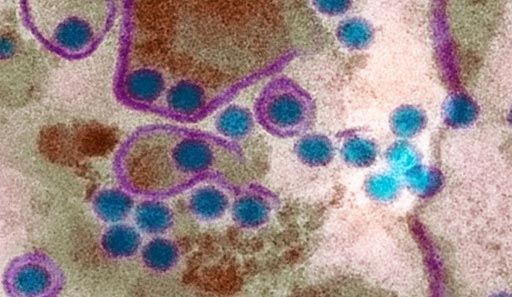

Image: People infected more than once with the mosquito-borne dengue virus (blue circles) are at greatest risk for the most severe, potentially fatal, forms of the disease (Photo courtesy of Science).

“Patients with severe secondary disease have high levels of a particular type of antibody that triggers a forceful immune response. This distinctive signature did not show up in patients with more mild illness,” said senior author Jeffrey V. Ravetch, professor at Rockefeller, “Our work sheds new light on the way in which the dengue virus co-opts antibodies produced as a result of the previous infection, using them to inflict more damage the second time around.”

Researchers have long thought that, when the virus infects a second time, it somehow takes advantage of antibodies that the immune system is still producing as a result of the first infection. But this does not explain why less than 15% of people who catch dengue for the second time develop full-blown hemorrhagic fever or shock.

Previous work in Prof. Ravetch’s lab suggested differences in antibodies might account for why only some people develop severe secondary infections. They showed that the structure of the Fc region of antibodies can influence an immune response by, for example, promoting inflammation versus calming it.

For the current study, first author Taia Wang, then a postdoc in the lab and now assistant professor at Stanford School of Medicine, and her collaborators examined the Fc regions of antibodies in blood collected from patients with mild and severe secondary dengue infections at Siriraj Hospital in Bangkok, Thailand. These people’s immune systems were still producing antibodies as a result of their first dengue virus infection, but the structure of these antibodies varied between individuals.

The researchers found that the dengue patients with more serious disease had high levels of antibodies whose Fc regions lack a particular sugar, a variation known to strongly activate immune cells. Experimentally, they found that activating signals from these antibodies aggravated the disease by leading to the destruction of blood-clotting cells – platelets. So when their platelet levels plummet, patients bleed abnormally—a hallmark of hemorrhagic fever. They found that the lower a patient’s platelet count, the more of these distinctive antibodies he or she tended to have.

“We found that some people’s immune systems respond to dengue infection by producing elevated levels of these pathogenic antibodies, which make them more vulnerable to a severe secondary dengue infection,” said Prof. Wang, “It’s not yet clear if they produce more of these highly activating antibodies even before they encounter the virus.”

The discovery of this antibody signature could help fight the disease in a number of ways. “Because we now know what to look for, it may become possible to identify patients at risk of severe illness, so they can receive intensive, supportive care early on,” said Prof. Ravetch, “It could also aid in the development of safe dengue vaccines that stimulate the immune system without triggering a secondary, potentially harmful response, and of new drugs designed to help patients recover by blocking the antibody signaling.”

Since dengue belongs to the same family of viruses as Zika, the implications go beyond this particular disease. “It will be important to consider the possibility that other, related viruses employ a similar strategy, and that infection with one may affect the subsequent response to another,” said Prof. Ravetch.

The study, by Wang TT et al, was published online January 27, 2017, in the journal Science.