AI-Powered Microscope Diagnoses Malaria in Blood Smears Within Minutes

Posted on 12 Feb 2026

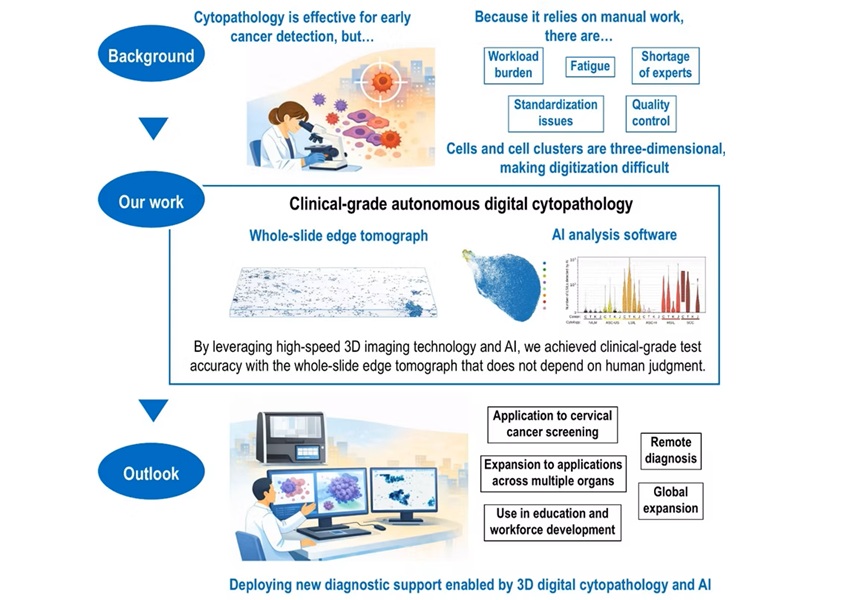

Malaria remains one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, killing hundreds of thousands each year, mostly in under-resourced regions where laboratory infrastructure is limited. Diagnosis still relies heavily on manual microscopy, a slow, labor-intensive process that can take 30 minutes per patient and limits the number of people who can be tested each day. Researchers have now developed an autonomous, artificial intelligence (AI)-powered microscope that can analyze blood samples in minutes, dramatically accelerating and standardizing malaria diagnosis even in remote, off-grid settings.

The device called Octopi has been developed by engineers at Stanford University (Stanford, CA, USA) and is a battery- or solar-powered robotic microscope built on an open software architecture that allows global customization. It combines low-cost optics with artificial intelligence to scan blood smears autonomously, eliminating the need for continuous human operation or internet connectivity.

Octopi works alongside a complementary tool called Inkwell, a passive, electricity-free mechanism that standardizes blood smear preparation. Inkwell uses capillary action to create uniform, microscope-ready slides containing a thin layer of roughly 20 million blood cells. Both systems are designed for affordability, portability, and deployment in regions where malaria is most prevalent.

Octopi can scan up to one million blood cells per minute, representing a 100-fold increase in efficiency compared with conventional manual microscopy. The system is sensitive enough to detect as few as 12 infected cells in a microliter of blood among millions of healthy cells, with near-100% specificity. By identifying a characteristic spectral shift in malaria-infected cells under ultraviolet light, the AI can rapidly count parasites and quantify disease severity.

The technology has been refined and tested over nearly a decade across nine countries in Africa and other regions, demonstrating reliable performance under real-world conditions. Its ability to deliver both diagnosis and parasite load data supports earlier treatment decisions and more accurate assessment of disease severity.

Faster, quantitative diagnosis could improve individual patient outcomes while also identifying asymptomatic carriers who unknowingly contribute to malaria transmission. Beyond malaria, Octopi’s open software model allows the same hardware to be retrained to detect other diseases identifiable by microscopy. Demonstrations have already shown successful adaptation for sickle cell anemia and tuberculosis without changing the device itself.

The researchers envision Octopi as a universal diagnostic platform, where new disease-detection models can be shared globally in an “app store”–style ecosystem. To scale this vision, the team is launching the Open Diagnostic Imaging Observatory Network (ODION) to enable clinicians and researchers worldwide to develop and deploy their own diagnostic applications.

“Currently, a human sits at a microscope looking at slides, hour by hour, counting the infected cells by hand. Each sample takes half an hour. A technician can do maybe 25 people a day – and that’s a 12-hour day,” said Manu Prakash, an associate professor at Stanford University and Octopi’s inventor. “For the first time, Octopi can now do an accurate diagnosis in minutes in the middle of nowhere with no other infrastructure. No power? No internet? No problem!”

Related Links:

Stanford University